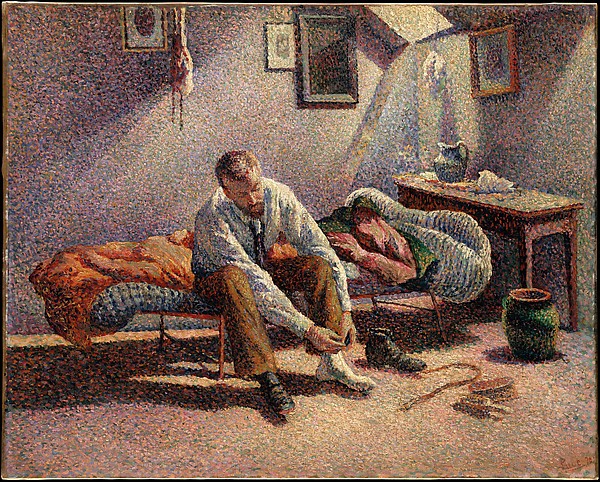

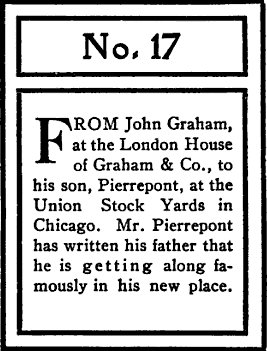

George Lorimer, an editor at the Saturday Evening Post, published a series of fictional letters in that magazine in which a father, John Graham, imparts advice to his son, Pierrepont, throughout the different stages of the young man’s life. The letters were then compiled in the hugely successful 1901 book Letters from a Self-Made Merchant to His Son.

London, October 24, 189—

Dear Pierrepont:

I’m glad to learn from your letter that you’re getting along so well in your new place, and I hope that when I get home your boss will back up all the good things which you say about yourself. For the future, however, you needn’t bother to keep me posted along this line. It’s the one subject on which most men are perfectly frank, and it’s about the only one on which it isn’t necessary to be. There’s never any use trying to hide the fact that you’re a jim-dandy—you’re bound to be found out. A man who does big things is too busy to talk about them. When the jaws really need exercise, chew gum.

Some men go through life on the Sarsaparilla Theory—that they’ve got to give a hundred doses of talk about themselves for every dollar which they take in; and that’s a pretty good theory when you’re getting a dollar for ten cents’ worth of ingredients. But a man who’s giving a dollar’s worth of himself for ninety-nine cents doesn’t need to throw in any explanations.

Of course, you’re going to meet fellows right along who pass as good men for a while, because they say they’re good men; just as a lot of fives are in circulation which are accepted at their face value until they work up to the receiving teller. And you’re going to see these men taking buzzards and coining eagles from them that will fool people so long as they can keep them in the air; but sooner or later they’re bound to swoop back to their dead horse, and you’ll get the buzzard smell.

Hot air can take up a balloon a long ways, but it can’t keep it there. And when a fellow’s turning flip-flops up among the clouds, he’s naturally going to have the farmers gaping at him. But in the end there always comes a time when the parachute fails to work. I don’t know anything that’s quite so dead as a man who’s fallen three or four thousand feet off the edge of a cloud.

The only way to gratify a taste for scenery is to climb a mountain. You don’t get up so quick, but you don’t come down so sudden. Even then, there’s a chance that a fellow may slip and fall over a precipice, but not unless he’s foolish enough to try short-cuts over slippery places; though some men can manage to fall down the hall stairs and break their necks. The path isn’t the shortest way to the top, but it’s usually the safest way.

Life isn’t a spurt, but a long, steady climb. You can’t run far up-hill without stopping to sit down. Some men do a day’s work and then spend six lolling around admiring it. They rush at a thing with a whoop and use up all their wind in that. And when they’re rested and have got it back, they whoop again and start off in a new direction. They mistake intention for determination, and after they have told you what they propose to do and get right up to doing it, they simply peter out.

I speak of these things in a general way, because I want you to keep in mind all the time that steady, quiet, persistent, plain work can’t be imitated or replaced by anything just as good, and because your request for a job for Courtland Warrington naturally brings them up. You write that Court says that a man who has occupied his position in the world naturally can’t cheapen himself by stepping down into any little piddling job where he’d have to do undignified things.

I want to start right out by saying that I know Court and his whole breed like a glue factory, and that we can’t use him in our business. He’s one of those fellows who start in at the top and naturally work down to the bottom, because that is where they belong. His father gave him an interest in the concern when he left college, and since the old man failed three years ago and took a salary himself, Court’s been sponging on him and waiting for a nice, dignified job to come along and steal him. But we are not in the kidnapping business.

The only undignified job I know of is loafing, and nothing can cheapen a man who sponges instead of hunting any sort of work, because he’s as cheap already as they can be made. I never could quite understand these fellows who keep down every decent instinct in order to keep up appearance, and who will stoop to any sort of real meanness to boost up their false pride.

They always remind me of little Fatty Wilkins, who came to live in our town back in Missouri when I was a boy. His mother thought a heap of Fatty, and Fatty thought a heap of himself, or his stomach, which was the same thing. Looked like he’d been taken from a joke book. Used to be a great eater. Stuffed himself till his hide was stretched as tight as a sausage skin, and then howled for painkiller. Spent all his pennies for cakes, because candy wasn’t filling enough. Hogged ’em in the shop, for fear he would have to give some one a bite if he ate them on the street.

The other boys didn’t take to Fatty, and they didn’t make any special secret of it when he was around. He was a mighty brave boy and a mighty strong boy and a mighty proud boy—with his mouth; but he always managed to slip out of anything that looked like a fight by having a sore hand or a case of the mumps. The truth of the matter was that he was afraid of everything except food, and that was the thing which was hurting him most. It’s mighty seldom that a fellow’s afraid of what he ought to be afraid of in this world.

Of course, like most cowards, while Fatty always had an excuse for not doing something that might hurt his skin, he would take a dare to do anything that would hurt his self-respect, for fear the boys would laugh at him, or say that he was afraid, if he refused. So one day during recess Jim Hicks dared him to eat a piece of dirt. Fatty hesitated a little, because, while he was pretty promiscuous about what he put into his stomach, he had never included dirt in his bill-of-fare. But when the boys began to say that he was afraid, Fatty up and swallowed it.

And when he dared the other boys to do the same thing and none of them would take the dare, it made him mighty proud and puffed up. Got to charging the bigger boys and the lounger around the post-office a cent to see him eat a piece of dirt the size of a hickory-nut. Found there was good money in that, and added grasshoppers, at two cents apiece, as a side line. Found them so popular that he took on chinch bugs at a nickel, and fairly coined money. The last I heard of Fatty he was in a Dime Museum, drawing two salaries—one as “The Fat Man,” and the other as “Launcelot, The Locust Eater, the Only Man Alive with a Gizzard.”

You are going to meet a heap of Fatties, first and last, fellows who’ll eat a little dirt “for fun” or to show off, and who’ll eat a little more because they find that there’s some easy money or times in it. It’s hard to get at these men, because when they’ve lost everything they had to be proud of, they still keep their pride. You can always bet that when a fellow’s pride makes him touchy, it’s because there are some mighty raw spots on it.

It’s been my experience that pride is usually a spur to the strong and a drag on the weak. It drives the strong man along and holds the weak one back. It makes the fellow with the stiff upper lip and the square jaw smile at a laugh and laugh at a sneer; it keeps his conscience straight and his back humped over his work; it makes him appreciate the little things and fight for the big ones. But it makes the fellow with the retreating forehead do the thing that looks right, instead of the thing that is right; it makes him fear a laugh and shrivel up at a sneer; it makes him live to-day on to-morrow’s salary; it makes him a cheap imitation of some Willie who has a little more money than he has, without giving him zip enough to go out and force luck for himself.

I never see one of these fellows swelling around with their petty larceny pride that I don’t think of a little experience of mine when I was a boy. An old fellow caught me lifting a watermelon in his patch, one afternoon, and instead of cuffing me and letting me go, as I had expected if I got caught, he led me home by the ear to my ma, and told her what I had been up to.

Your grandma had been raised on the old-fashioned plan, and she had never heard of these new-fangled theories of reasoning gently with a child till its under lip begins to stick out and its eyes to fill with tears as it sees the error of its ways. She fetched the tears all right, but she did it with a trunk strap or a slipper. And your grandma was a pretty substantial woman. Nothing of the tootsey-wootsey about her foot, and nothing of the airy-fairy trifle about her slipper. When she was through I knew that I’d been licked—polished right off to a point—and then she sent me to my room and told me not to poke my nose out of it till I could recite the Ten Commandments and the Sunday-school lesson by heart.

There was a whole chapter of it, and an Old Testament chapter at that, but I laid right into it because I knew ma, and supper was only two hours off. I can repeat that chapter still, forward and backward, without missing a word or stopping to catch my breath.

Every now and then old Doc Hoover used to come into the Sunday-school room and scare the scholars into fits by going around from class to class and asking questions. That next Sunday, for the first time, I was glad to see him happen in, and I didn’t try to escape attention when he worked around to our class. For ten minutes I’d been busting for him to ask me to recite a verse of the lesson, and, when he did, I simply cut loose and recited the whole chapter and threw in the Ten Commandments for good measure. It sort of dazed the Doc, because he had come to me for information about the Old Testament before, and we’d never got much beyond, And Ahab begat Jahab, or words to that effect. But when he got over the shock he made me stand right up before the whole school and do it again. Patted me on the head and said I was “an honor to my parents and an example to my playmates.”

I had been looking down all the time, feeling mighty proud and scared, but at that I couldn’t help glancing up to see the other boys admire me. But the first person my eye lit on was your grandma, standing in the back of the room, where she had stopped for a moment on her way up to church, and glaring at me in a mighty unpleasant way.

“Tell ’em, John,” she said right out loud, before everybody.

There was no way to run, for the Elder had hold of my hand, and there was no place to hide, though I reckon I could have crawled into a rat hole. So, to gain time, I blurted out:

“Tell ’em what, mam?”

“Tell ’em how you come to have your lesson so nice.”

I learned to hate notoriety right then and there, but I knew there was no switching her off on to the weather when she wanted to talk religion. So I shut my eyes and let it come, though it caught on my palate once or twice on the way out.

“Hooked a watermelon, mam.”

There wasn’t any need for further particulars with that crowd, and they simply howled. Ma led me up to our pew, allowing that she’d tend to me Monday for disgracing her in public that way—and she did.

That was a twelve-grain dose, without any sugar coat, but it sweat more cant and false pride out of my system than I could get back into it for the next twenty years. I learned right there how to be humble, which is a heap more important than knowing how to be proud. There are mighty few men that need any lessons in that.

Your affectionate father,

John Graham.