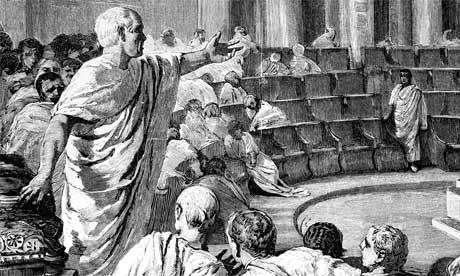

Welcome back to our series on Classical Rhetoric. Today we’re kicking off a five-part segment on the Five Canons of Rhetoric. As you remember from our brief introduction to classical rhetoric, the Five Canons of Rhetoric constitute a system and guide on crafting powerful speeches and writing. It’s also a template by which to judge effective rhetoric. The Five Canons were brought together and organized by the Roman orator Cicero, in his treatise, De Inventione, written around 50 BC. 150 years later in 95 AD, the Roman rhetorician Quintilian explored the Five Canons in more depth in his landmark 12-volume textbook on rhetoric, Institutio Oratoria. His textbook, and consequently the Five Canons of Rhetoric, went on to become the backbone of rhetorical education well into the medieval period.

Enough with the history. What are the Five Canons of Rhetoric? Glad you asked.

The Five Canons of Rhetoric are:

- inventio (invention): The process of developing and refining your arguments.

- dispositio (arrangement): The process of arranging and organizing your arguments for maximum impact.

- elocutio (style): The process of determining how you present your arguments using figures of speech and other rhetorical techniques.

- memoria (memory): The process of learning and memorizing your speech so you can deliver it without the use of notes. Memory-work not only consisted of memorizing the words of a specific speech, but also storing up famous quotes, literary references, and other facts that could be used in impromptu speeches.

- actio (delivery): The process of practicing how you deliver your speech using gestures, pronunciation, and tone of voice.

If you’ve taken a public speaking class, you were probably taught a version of The Five Canons. They also form the foundation of many composition courses.

Over the next few weeks, we’ll be taking a look at each of the Five Canons separately and exploring how we use them in everyday situations to be more effective communicators. Ready, to get started? Let’s kick things off by talking about the first Canon of Rhetoric: Invention.

What Is Invention?

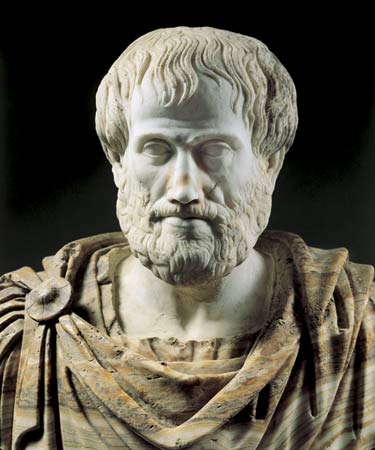

Invention, according to Aristotle, involves “discovering the best available means of persuasion.” It may sound simple, but Invention is possibly the most difficult phase in crafting a speech or piece of writing as it lays the groundwork for all the other phases; you must start from nothing to build the framework of your piece. During the Invention Phase, the goal is to brainstorm ideas on what you’re going to say and how you’re going to say it in order to maximize persuasion. Any good orator or writer will tell you they probably spend more time in the Invention step than they do any of the others.

Take Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia. Yeah, the man is polarizing and a lightning rod for controversy, but lawyers and jurists across the political spectrum recognize him as one of the best legal writers in the history of the Supreme Court. He’s able to take complex issues and arguments and distill them into short, powerful, and often witty sentences and paragraphs. Even if you don’t agree with the outcome of his opinions, you’re often left thinking, “Damn, that was a really good argument!”

What’s the secret to Justice Scalia’s rhetorical ability? Spending lots and lots of time in the Invention Phase. In an interview about his writing process, Scalia explained that he goes through “a lengthy germination process” for ideas before he puts pen to paper (or fingers to keyboard). Scalia brainstorms in his car while driving home from work and at the gym while exercising. This germination process lasts anywhere from a few days to even a few weeks. But the time invested in simply thinking and brainstorming pays off when he finally gets down to writing. I find this to be the case in my own life as well; my best posts are those which I allow to percolate in my brain for a long time, months, even years. I’m kicking around ideas when I’m brushing my teeth and taking a walk. When I finally sit down to write, the ideas come tumbling out, already nicely aged and seasoned.

Things to Consider in the Invention Phase

So what sorts of things should you be thinking about during the Invention Phase? Without some direction and guidance, brainstorming can often be fruitless and frustrating. Pondering the following elements can increase the effectiveness of your Invention sessions.

Your audience. One of the key factors in crafting a persuasive piece of rhetoric is tailoring your message to your specific audience. Find out to the best of your ability the overall demographics and cultural background of your audience. What does your audience fear? What are their desires? What are their needs? This information will help you decide what sorts of facts to incorporate into your rhetoric as well as help you determine which means of persuasion would be the most effective to employ.

Your evidence. When planning your speech or writing, collect any and every type of evidence you can find. Evidence could be facts, statistics, laws, and individual testimonies. It’s always good to have a nice blend, but remember different audiences are persuaded by different types of evidence. Some people need cold, hard facts and statistics in order to be persuaded. Others find the testimony of peers or a reputable authority to be more convincing. Part of getting to know your audience is figuring out what kinds of evidence they will find most credible and compelling.

The means of persuasion. You remember the three means of persuasion, right? Pathos, logos, and ethos? This is the time when you want to determine which of the three persuasive appeals you’ll use in your speech. Ideally, you’d have a nice mixture of all three, but again, different audiences will be better persuaded by different appeals. Using pathos (appeal to emotion) to convince a room full of scientists that you have discovered cold fusion probably won’t get you very far. A focus on logos would work much better. Again, it’s all about suiting your rhetoric to your audience.

Timing. People are receptive to certain ideas at different times depending on context. People often advise couples not to go to bed angry, to work out their problems before hitting the sack. But at night we’re tired and cranky; our defenses are down. Trying to convey your side of things at this time frequently results in a small issue blowing up into something much bigger. On the other hand, a good night’s sleep often helps put things in perspective. You’ll likely find your spouse more willing to hear you out in the morning. As it is in marriage, so it is with everything in life; the importance of timing cannot be underestimated. Present a cost-cutting idea at work the same day five of everyone’s favorite employees were laid off, and you’ll get a icy, hostile reception. Present it six months later and people will actually listen.

Another aspect of timing is the duration of your speech or writing. In some instances a long, well-developed, and nuanced speech is appropriate; other times, a shorter, and more forceful presentation will be more effective. Again, it often depends on your audience and the context of your speech.

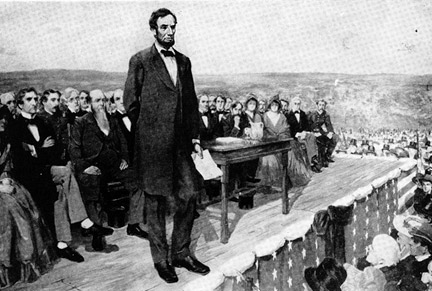

Abraham Lincoln was a master of timing. His Gettysburg Address is one of the most famous speeches in history. Many people don’t know that Lincoln actually wasn’t the keynote speaker that day; rather, that honor fell to renowned orator, Edward Everett. Everett delivered a two hour speech that displayed some of the finest skill in oration and rhetoric; he held the audience in rapt attention. Lincoln took to the stand and delivered his address in less than five minutes. While the contemporary audience was not overly impressed, Everett knew he had been witness to greatness. He wrote Lincoln, “I should be glad if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes.” And of course, 150 years later, no one quotes Everett or even remembers he spoke at Gettysburg, but everyone remembers Lincoln and are familiar with his words. Timing matters.

Format of argument. So you have a vague idea of what you’re supposed to write or talk about. The hard part is taking that vague idea and organizing it into a concrete theme or thesis. Without some guidance on how to do this, a man can rack his brain for hours and not get anywhere. Fortunately for us, the ancient rhetoricians left us some nifty little cheat sheets on developing the format and theme for our arguments, which is where we turn next.

Ancient Helps for the Invention Phase

Stasis. Stasis is a procedure designed to help a rhetorician develop and clarify the main points of his argument. Stasis consists of four types of questions a speaker asks himself. They are:

- Questions of fact: What is it exactly that I’m talking about? Is it a person? An idea? A problem? Does it really exist? What’s the source of the problem? Are there facts to support the truth of this opinion?

- Questions of definition: What’s the best way to define this idea/object/action? What are the different parts? Can it be grouped with similar ideas/objects/actions?

- Questions of quality: Is it good or bad? Is it right or wrong? Is it frivolous or important?

- Questions of procedure/jurisdiction: Is this the right venue to discuss this topic? What actions do I want my reader/listener to take?

These questions may sound completely elementary, but trust me, when you’re struggling to get your mind around an idea for a speech or writing theme, stasis has an almost magical way of focusing your thinking and helping you develop your argument. Don’t skip out on it.

Topoi (Topics of Invention). Topoi, or topics, consist of a set of categories that are designed to help a writer or speaker find relationships among ideas, which in turn helps organize his thoughts into a solid argument. Aristotle organized the different rhetorical topics in his treatise The Art of Rhetoric. He divided the topics into two large categories: common and special. We’ll focus on common topics as they’re more general and applicable to every day rhetorical situations. (If you’d like more info on special topics see here.) Below, I’ve listed a few of the common topics that are especially helpful in forming arguments.

- Definition. My classics professor crammed it into my head that in any rhetorical debate, definitions are vital. Whoever can dictate and control the meaning of a word or idea, will typically win. Politicians know this and spend a lot of energy working to frame and define the debate in their own terms and with their own spin. The topic of definition requires an author to determine how he would classify the idea, what its substance is, and to what degree it has that substance.

- Comparison. You’re probably familiar with this one from your middle school days when you had to write compare and contrast essays. It’s a great way to explore and organize. But the real power of comparison lies in its ability to help you develop powerful analogies and metaphors that stick with your audience.

- Cause and Effect. Perhaps you’re in a city hall meeting arguing against a new ordinance that requires restaurants to display nutrition information on all their food. You could use cause and effect as an effective way to persuade your listeners that it’s not a good idea. Using strong, factual evidence, present some of the possible detrimental effects of implementing the ordinance. (i.e. expensive for businesses, extra costs to city government to regulate, etc.)

- Circumstance. This topic looks at what is possible or impossible based on circumstances. With the topic of circumstance, you can also attempt to draw conclusions on future facts or events by referring to events in the past. “I know the sun will rise tomorrow because it has risen every day for thousands of years,” is a very simple example of the topic of circumstance in action.

Stasis and the topoi are just starting points in helping you organize your thoughts and arguments.

That does it for today. I hope you learned something you could apply in your own life. Next, time we’ll be discussing the canon of arrangement.

Classical Rhetoric 101 Series

An Introduction

A Brief History

The Three Means of Persuasion

The Five Canons of Rhetoric – Invention

The Five Canons of Rhetoric – Arrangement

The Five Canons of Rhetoric – Style

The Five Canons of Rhetoric – Memory

The Five Canons of Rhetoric – Delivery

Logical Fallacies

Bonus! 35 Greatest Speeches in History