This is Part II in a series designed to give readers a primer on the simple basics of some of the major periods of Western art in the hopes of giving you something to say on your next date to the museum and a deeper appreciation for art in general. Part I covered the basics of Renaissance Art.

The Basics of Baroque Art

Time Period: 1600s-1700s

Background: When Martin Luther penned his 95 Theses in 1517, he set off a movement that would forever change the world: the Protestant Reformation. His criticisms of the Catholic Church and arguments for things like the supreme authority of the Scriptures and justification by faith alone would spread throughout Europe via the printing press, making converts and starting new Protestant denominations.

In response, the Catholic Church launched its own internal reformation to both clean up corruption and clearly define its doctrines and theology. This Counter-Reformation found its most important expression in the Council of Trent, called by Pope Paul III in 1545. While the Council took steps to reform internal abuses, it made no attempt to compromise with Protestants on matters of doctrine; instead, the Church strongly reaffirmed the truth of the positions the Protestants had attacked. This re-infused the Catholic faith with new vigor and confidence.

Yet a lesser known consequence of the Council of Trent was its effect on art.

Part of the Church’s reform effort was to educate its members, helping them to understand more about their faith. This was no easy task as most people were illiterate during this time. The Council of Trent declared that art should be used to explain the profound dogmas of the faith to everyone, not just the educated. To accomplish this, religious art was to be direct, emotionally persuasive, and powerful-designed to fire the spiritual imagination and inspire the viewer to greater piety.

New denominations like the Calvinists believed that churches and church services should be simple, stripped-down affairs. But the Council argued that a God of greatness and power should be worshiped with the kinds of rituals, ceremonies, and churches befitting these divine qualities. This affirmation of the beauty and grandiosity of expressions of faith found its way into Baroque art.

Things to Look for in Baroque Art:

- Images are direct, obvious, and dramatic.

- Tries to draw the viewer in to participate in the scene.

- Depictions feel physically and psychologically real. Emotionally intense.

- Extravagant settings and ornamentation.

- Dramatic use of color.

- Dramatic contrasts between light and dark, light and shadow.

- As opposed to Renaissance art with its clearly defined planes, with each figure placed in isolation from each other, Baroque art has continuous overlapping of figures and elements.

- Common themes: grandiose visions, ecstasies and conversions, martyrdom and death, intense light, intense psychological moments.

Examples:

The Ecstasy of St. Teresa, by Giovanni Lorenzo Bernini, 1652. A common theme for Baroque artists was the miraculous moment where the divine met the earthly, the sacred intruded upon the profane. St. Teresa was a mystic nun who recorded an experience in which an angel came down and pierced her innards with the flaming arrow of divine love. The pain was great yet sweet and brought her into ecstasy with God. The Baroque use of light is also on display; the wooden rays come down in spectacular fashion and are lit by a yellow paneled window above the sculpture.

The Ecstasy of St. Teresa, by Giovanni Lorenzo Bernini, 1652. A common theme for Baroque artists was the miraculous moment where the divine met the earthly, the sacred intruded upon the profane. St. Teresa was a mystic nun who recorded an experience in which an angel came down and pierced her innards with the flaming arrow of divine love. The pain was great yet sweet and brought her into ecstasy with God. The Baroque use of light is also on display; the wooden rays come down in spectacular fashion and are lit by a yellow paneled window above the sculpture.

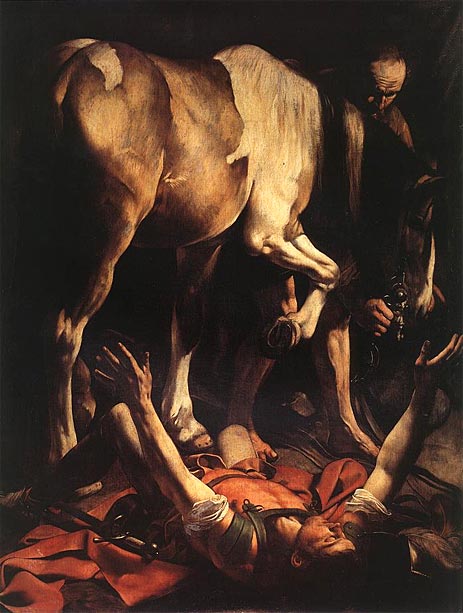

The Conversion on the Way to Damascus, by Caravaggio, 1601. Caravaggio is perhaps my favorite painter of any period, and this is my favorite painting of his. Depicted is the moment where Saul (soon to be Paul) has a conversion experience on the road to Damascus. Again we see the Baroque theme of the divine suddenly intruding into the earthly sphere. Caravaggio was a master at using shadow and light to heighten the drama and meaning of his paintings. Here God’s light has knocked Saul off his horse, and his arms are stretched out in a funnel shape to accept the light. Meanwhile the man and the horse, who symbolize the ordinary earthly world and are not privy to the full experience, are deep in shadow.

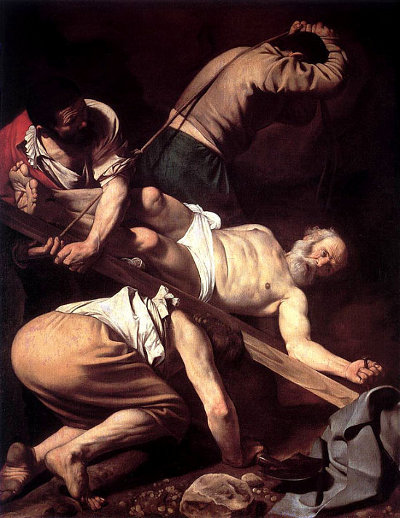

The Crucifixion of Saint Peter, by Caravaggio, 1601. In contrast to the idealized, noble, classical human forms favored by Renaissance artists, Caravaggio preferred to paint scenes and people as the eye would see them, natural flaws included. He did not feel that a painting had to be sentimentalized to be powerful, believing instead that the intrinsic nature of the scene, the eloquence captured in the figures’ real poses, was educationally effective. His paintings were so realistic that patrons sometimes rejected them as too “vulgar.” In this painting, St. Peter is being crucified. He asked to be hung from his cross upside-down as not to imitate his Lord. The divine light shines on Peter while the faces of the Romans are obscured by shadows. Peter seems to be much heavier than one would expect-three men are struggling to lift him, symbolizing the great weight of their crime.

The Crucifixion of Saint Peter, by Caravaggio, 1601. In contrast to the idealized, noble, classical human forms favored by Renaissance artists, Caravaggio preferred to paint scenes and people as the eye would see them, natural flaws included. He did not feel that a painting had to be sentimentalized to be powerful, believing instead that the intrinsic nature of the scene, the eloquence captured in the figures’ real poses, was educationally effective. His paintings were so realistic that patrons sometimes rejected them as too “vulgar.” In this painting, St. Peter is being crucified. He asked to be hung from his cross upside-down as not to imitate his Lord. The divine light shines on Peter while the faces of the Romans are obscured by shadows. Peter seems to be much heavier than one would expect-three men are struggling to lift him, symbolizing the great weight of their crime.

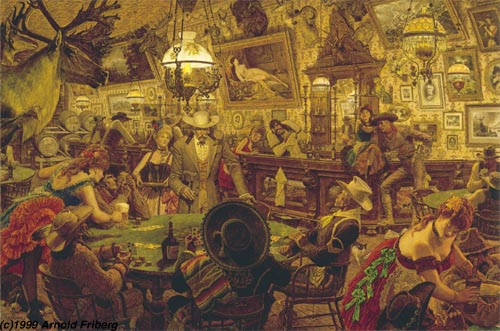

The Four Continents, by Peter Paul Rubens, 1615. Peter Paul Rubens was a leading Counter-Reformation painter and brought the energy, sensuality, and drama of Baroque art not only to religious works but also to historical and mythological themes (and sometimes a combination of all three). The Flemish artist’s work was influenced by both his education in Antwerp and a trip to Rome, elements which became a masterful synthesis of Renaissance and Baroque style. In The Four Continents you can see the Baroque characteristics of vivid color, physicality, and overlapping figures. Symbolizing the spread of the Catholic Church all around the world, the depiction of the four continents as women was a common theme in Counter-Reformation art, especially in Jesuit churches. Ruben’s penchant for depicting women with some meat on their bones led to the familiar adjective “Rubenesque” for describing full-figured ladies.

Descent from the Cross, by Rembrandt, 1634. While Rembrandt is perhaps best remembered for his portraits, he was also a master Baroque painter of landscapes and religious themes. In all his paintings and etchings he strove for “the greatest and most natural movement.” In his Descent from the Cross, we once again see the Baroque signature of an emotional scene heightened by the dramatic use of light and shadow. The light shines on Christ’s body, the faithful women who stood by him, and the shroud in which he will return to life.

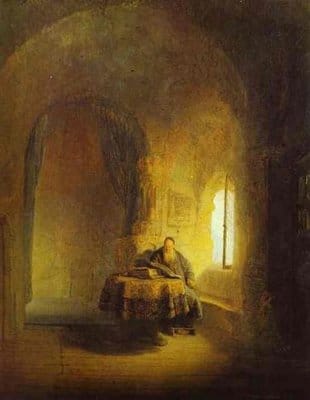

My favorite Rembrandts are his Philosopher series, which at this point I probably don’t have to point out, employ shadow and light brilliantly:

Philosopher in Meditation

Philosopher in Meditation

Philosopher with an Open Book

Philosopher with an Open Book

Philosopher Reading

Philosopher Reading

The Basics of Art Series

The Renaissance

The Baroque Period

The Romantic Period