“For every one of us, living in this world

means waiting for our end. Let whoever can

win glory before death. When a warrior is gone,

that will be his best and only bulwark…

Endure your troubles today. Bear up

and be the man I expect you to be.”

For the men of 10th century Europe, these were words to live by. Theirs was a time before the chivalric era, where knightly romance was hardly a dream and virtue and honor had yet to be made into a formal code of conduct. These were the men of the Dark Ages, members of the many Germanic tribes that once roamed across Northern Europe. Their code was a code not of chivalry, but of raw courage, in which strength of character was the greatest, and often the only reward.

Beowulf is a portrait of these virtues. Written in the most primitive form of our own language, it is in many ways the forerunner of every other heroic tale in English literature. King Arthur and his knights, the ‘Big Men’ of American folklore, and even our modern superheroes owe much to Beowulf, a hero whose story speaks as strongly today as it did a thousand years ago.

The poem tells of Beowulf’s battles against three monsters in two stages of his life. In his youth, he frees Denmark from the creature Grendel and his vengeful mother, while in his old age he is forced to save his own people, the Geats, from a savage fire-breathing dragon. Though the challenges Beowulf faces seem far beyond anything we would ever expect to encounter ourselves, his story nonetheless portrays the virtues that every good man must follow, no matter how incredible his accomplishments.

A man is defined by his actions (or lack thereof). Although the poem has its characters, it often seems that the real stars of the show are the deeds the characters commit. The story itself is essentially plot-driven, or constructed by events. The characters in the poem are literally defined by what they do, creating a narrative where the quality of a man is proven solely by his deeds.

The Danish king Hrothgar’s generosity is shown by his construction of a great feasting-hall, a place to dole out gifts and treasures to his people. Upon meeting Hrothgar to free the Danes from the raids of the Grendel, Beowulf himself proves the integrity of his intentions by recalling how he has long defended his own people from many enemies. These words and promises are subsequently backed up by actions, proving that for the hero, words and deeds are inextricably linked.

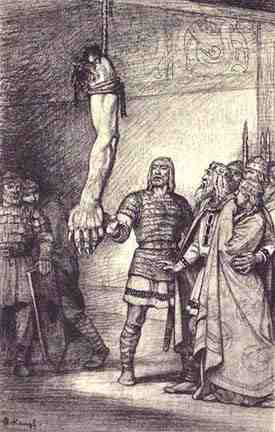

In contrast, a man purely of words-without-actions is seen as a coward. The character Unferth is shown as a foil to Beowulf. A man of wit but not works, he accuses the hero of exaggerating his prowess and taunts him that he will fall prey to Grendel that very night. Beowulf responds in the best way he can, by hanging Grendel’s bloodied arm from the ceiling of the hall the next morning. Naturally, as is any coward in the face of such deeds, Unferth is left speechless.

Honor is the greatest reward. For Beowulf, the only prize worth winning is to do something worthy of remembrance. In the poem, good deeds are shown to have everlasting merit – they leave an indelible mark on the world, permanently impacting and shaping it, destined to live on in the memories of those to follow.

Against such a prize, material rewards pale by comparison. Beowulf cares little for wealth and personal gain. Though he is lavished with treasures by the Danes for his defeat of Grendel, he gives them all away as tribute to his uncle, the king of the Geats. Though he eventually succeeds his uncle, he does so without ambition, inheriting the crown only after the death of the king’s two heirs. Even the fire-dragon’s magnificent horde, bartered in Beowulf’s final battle with his own life, is treated with contempt and buried with the fallen hero:

“They let the ground keep that ancestral treasure,

gold under gravel, gone to earth,

as useless to men now as ever it was.”

In the poem, the virtue of recklessness did not mean acting impetuously, but rather for the honor of the deed itself. Knowing full well the risks involved, the reckless man chose to act without regard for material reward. A hero will ultimately lose his wealth and material gains, but his actions cannot be taken from him; that is the treasure that does not tarnish, for true honor can never be lost.

A man’s resolve means more than the outcome. Linked to this sense of recklessness is the belief that each man is bound to a particular fate which is constantly present, “unknowable but certain.” Life during the Dark Ages was harsh, and the men of the time were accustomed to loss and failure, realizing that despite their efforts, “fate goes ever as fate must.” No matter how strongly it is desired or sought for, success could never be certain.

Instead, the only thing a man could be certain of are those things he had total control over: his will and his resolve to carry it out. Though the outcome was ultimately out of his hands, a man could still choose to do the right thing in a given situation. Once he had chosen, retreat would mean dishonor.

“I had a fixed purpose when I put to sea…

I meant to perform to the uttermost

what your people wanted or perish in the attempt…

And I shall fulfill that purpose,

prove myself with a proud deed

or meet my death.”

Beowulf’s oath before his fight with Grendel is not to victory, for that is not for him to decide. Rather, he swears to unyielding resolve in his protection of the Danes. For him, death was better than retreat, for “a warrior will sooner die than live a life of shame.”

The greatest of all virtues is courage. Well before he received wide acclaim for his own epic, The Lord of the Rings, a certain Oxford scholar named J. R. R. Tolkien identified courage as the central theme of Beowulf. Although it has been given hundreds of different meanings, from ‘physical strength’ to simple ‘bravery,’ the virtue of courage is taken to mean something very specific in the poem – the will to do the right thing even in the face of total defeat.

Unlike so many of our modern heroes, whose stories often end with them riding into the sunset (in anticipation of yet another serialized installment), Beowulf’s story ends in tragedy. Aged, weaponless, and abandoned by all but one of his closest friends, he dies in battle against the dragon, leaving his people without an heir and at the utter mercy of the invading tribes.

Unlike so many of our modern heroes, whose stories often end with them riding into the sunset (in anticipation of yet another serialized installment), Beowulf’s story ends in tragedy. Aged, weaponless, and abandoned by all but one of his closest friends, he dies in battle against the dragon, leaving his people without an heir and at the utter mercy of the invading tribes.

But victory does not make the hero. Beowulf is strong, a resolute man of action and honor, but it is precisely the fact that he is doomed to such a bleak end that makes him so truly heroic. Tolkien understood him as a man “caught in the chains of circumstance” who dies with his back “to the wall.” Provoked by a threat to its treasure, the dragon sets his homeland ablaze, forcing Beowulf to carry out his duty as protector of his people to its bitter end. Beowulf knows that he has no hope of surviving the battle but chooses to fight it nonetheless.

True courage bespeaks of the poems central theme, “the exaltation of undefeated will.” It is one thing to act honorably for honor’s sake, but for a man to live by his virtues, even when he knows it will mean his total defeat, is seen as the pinnacle of heroism. The men living in the wild, barbaric centuries of the Dark Ages knew well that all men feel loss, all men face defeat, and sooner or later, all men will die. But to them, courage was stronger than death. Even the greatest foe, be it Grendel, the dragon, or any other surrogate for war, famine, and the infinitely more monstrous demons of real life, cannot conquer the will that chooses death before surrender. A bleak ending to be sure, but one that is not without honor. As Tolkien himself quotes, “defeat is no refutation” against the courage of the hero.

Further Reading

There are many Modern English translations of Beowulf, but one of the best is Seamus Heaney’s 1999 translation, which is the one I quoted from. A more literal (and free) translation can be found here on “Beowulf in Cyberspace.”