A few weeks ago, we published an article on the Manly Tradition of the Pocket Notebook. For that piece, we dug through old books to find references to how pocket notebooks had been used this past century by men in different walks of life. In the process of compiling those excerpts, we came across intriguing references to how some of the famous men of history used their pocket notebooks and decided to put together a whole post exploring that subject.

The result is this look at how 20 famous men used their pocket notebooks. The list is hardly comprehensive; the practice was so widespread among eminent men that it would likely be easier to compile a list of famous men who did not use them, than did. And the choices are a bit eccentric; men who were famous for their interesting and numerous notebooks are well-represented but also included are a few from the past and present that just happened to cross our path during the course of our research. Where images of the notebooks were available they have been shown; in their absence a description will have to do. These caveats aside, we hope you will find reading about this manly practice as inspiring and fascinating as researching and writing about it was for us.

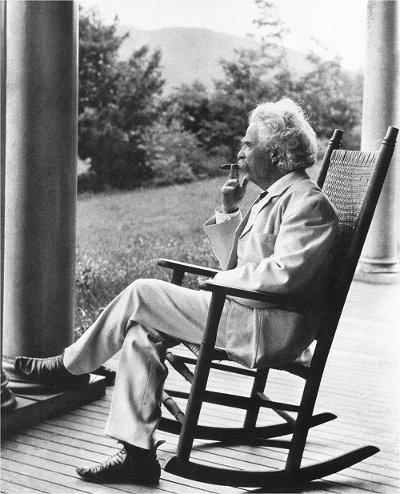

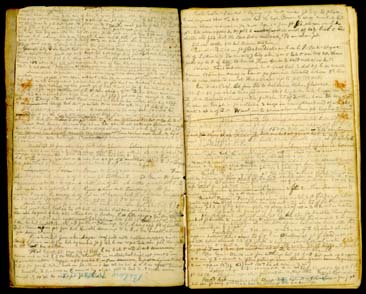

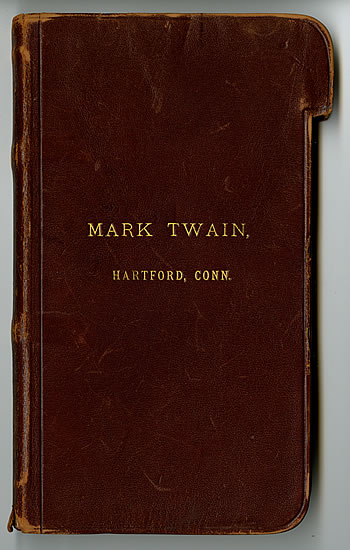

Mark Twain

Twain’s first pocket notebooks were purchased in 1857 at the age of 21 during his training to become the “cub” pilot of a steamboat on the Mississippi River. He felt confident that the job would be fairly easy to learn but found he could not remember the instructions his teacher, Horace Bixby, imparted to him. Bixby advised Clemens, “My boy, you must get a little memorandum-book, and every time I tell you a thing, put it down right away. There’s only one way to be a pilot, and that is to get this entire river by heart. You have to know it just like A B C.” Clemens accepted Bixby’s advice and thus began a lifelong relationship with the pocket notebook.

Twain’s first pocket notebooks were purchased in 1857 at the age of 21 during his training to become the “cub” pilot of a steamboat on the Mississippi River. He felt confident that the job would be fairly easy to learn but found he could not remember the instructions his teacher, Horace Bixby, imparted to him. Bixby advised Clemens, “My boy, you must get a little memorandum-book, and every time I tell you a thing, put it down right away. There’s only one way to be a pilot, and that is to get this entire river by heart. You have to know it just like A B C.” Clemens accepted Bixby’s advice and thus began a lifelong relationship with the pocket notebook.

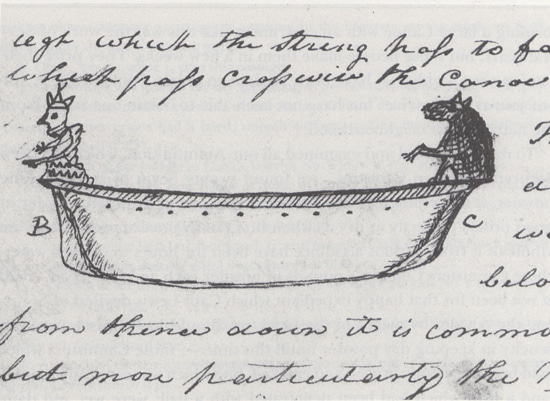

Twain’s notebook as a cub pilot

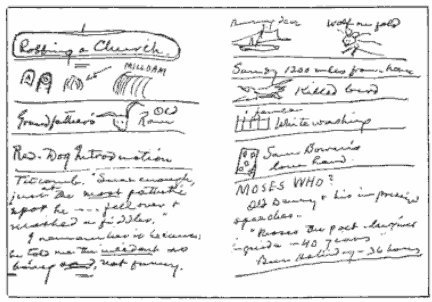

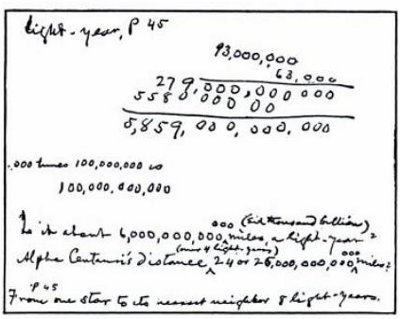

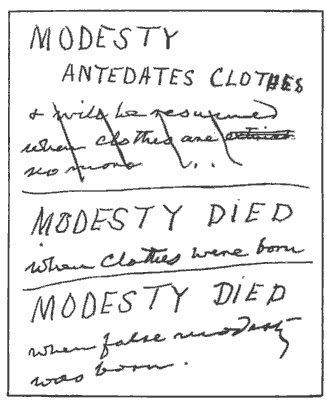

Twain kept 40-50 pocket notebooks over four decades of his life. He often began one before embarking on a trip. He filled the notebooks with observations of people he met, thoughts on religion and politics, drawings and sketches of what he saw on his travels, potential plots for books, and even ideas for inventions (he filed 3 patents during his lifetime). Many of his entries consist of the short, witty, pithy sentences he is famous for. He felt that if he did not write such things down as they came to his mind he would quickly forget them. He would also record little snippets in his notebooks of what had happened that day, such as what he had eaten and who he had seen. And finally, he wrote dirty jokes in the back of them.

Listing ideas for a title page.

Figuring out a light year.

He had his leather bound notebooks custom made according to his own design idea. Each page had a tab; once a page had been used, he would tear off its tab, allowing him to easily find the next blank page for his jottings:

Alexis de Tocqueville

On his two year tour of America and Canada, Tocqueville’s most important tools were the notebooks he made himself by folding and stitching sheets of paper together. In all, he filled 15 notebooks with his observations, thoughts, and impressions of his travels through North America. He organized his notebook pages into alphabetized headings like “Jury” and “Bankruptcy” and also kept a section for conversations and interviews. Two of his notebooks were exclusively devoted to legal issues. As he sat upon stagecoaches and steamboats, he would wrestle with the notes and reflections he had made, trying to distill out a “general truth” that tied them together and pointed to a more important and overarching idea. The result of this brain sweat were insights about the American people that still ring true to this day; the result of his notebooking keeping was Democracy in America; many of his notes made it verbatim into that classic book.

On his two year tour of America and Canada, Tocqueville’s most important tools were the notebooks he made himself by folding and stitching sheets of paper together. In all, he filled 15 notebooks with his observations, thoughts, and impressions of his travels through North America. He organized his notebook pages into alphabetized headings like “Jury” and “Bankruptcy” and also kept a section for conversations and interviews. Two of his notebooks were exclusively devoted to legal issues. As he sat upon stagecoaches and steamboats, he would wrestle with the notes and reflections he had made, trying to distill out a “general truth” that tied them together and pointed to a more important and overarching idea. The result of this brain sweat were insights about the American people that still ring true to this day; the result of his notebooking keeping was Democracy in America; many of his notes made it verbatim into that classic book.

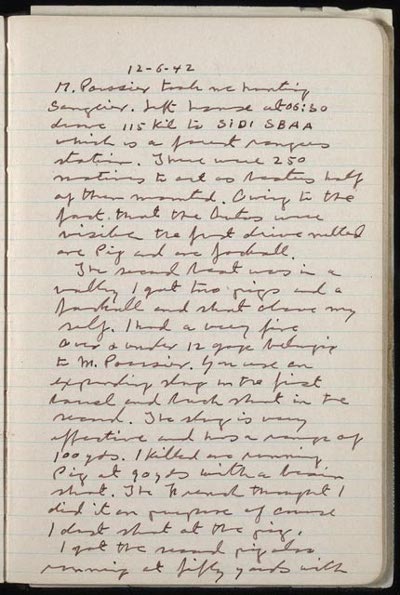

George S. Patton

Patton’s habit of pocket notebook keeping began after his freshman year at West Point. His first year had not gone well; he struggled with dyslexia and failed mathematics, forcing him to repeat his “plebe” year in the fall. He returned to school in 1905 with a steely dedication to this time be a success, and he started a small black leather notebook to help keep himself on track. He used his notebook to record daily happenings, explore ideas of leadership and war strategy, draw diagrams, and even pen poetry on love. But its most important use was as a place to write down the affirmations and principles that would guide his journey toward his ultimate goal- becoming a great general:

Patton’s habit of pocket notebook keeping began after his freshman year at West Point. His first year had not gone well; he struggled with dyslexia and failed mathematics, forcing him to repeat his “plebe” year in the fall. He returned to school in 1905 with a steely dedication to this time be a success, and he started a small black leather notebook to help keep himself on track. He used his notebook to record daily happenings, explore ideas of leadership and war strategy, draw diagrams, and even pen poetry on love. But its most important use was as a place to write down the affirmations and principles that would guide his journey toward his ultimate goal- becoming a great general:

“Do your damdest always.”

“Always do more than is required of you.”

“You can be what you will to be.”

In 1921 Patton began another important pocket notebook-this time a field notebook where he complied his thoughts on war and the qualities of successful soldiers-ideas that had been percolating during the first decade of his military career. On the notebook’s cover page he wrote: “SUCCESS IN WAR DEPENDS UPON THE GOLDEN RULE OF WAR. SPEED-SIMPLICTY-BOLDNESS.” The pages of the notebook were filled with Patton’s maxims, such as:

“War means fighting. Fighting means killing, not digging trenches.”

“Find the enemy, attack him, invade his land, raise hell while you’re at it.”

“Officers must be made to care for their men. That is the Sole Duty of All Officers.”

But this tough general didn’t just use his field book for battlefield musings.

During WWII, a young German priest was surprised to come upon Patton sitting in a medieval church which had been miraculously spared destruction. The hardened general sat in a pew with his notebook and a pencil, quietly contemplating and sketching the stained glass windows.

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson, a devoted early riser, would begin each day by taking measurements of the weather such as temperature, wind speed, and precipitation. And wherever he found himself in the world, whether at Monticello, France, or the White House, he would also make notes of things like the migration of birds, the growth of plants and flowers, and observations on geography and climate. To take these measurements, he carried a whole host of tools in his pocket, including a thermometer, a surveying compass, a level, writing instruments, and even a mini globe. He also carried a small notebook made up of ivory leaves on which to record his observations. He would write down his measurements in pencil and in the evening transfer the data to seven large notebooks, each devoted to a different subject. He would then erase the ivory plates, readying them for another day of scientific inquiry.

Thomas Jefferson, a devoted early riser, would begin each day by taking measurements of the weather such as temperature, wind speed, and precipitation. And wherever he found himself in the world, whether at Monticello, France, or the White House, he would also make notes of things like the migration of birds, the growth of plants and flowers, and observations on geography and climate. To take these measurements, he carried a whole host of tools in his pocket, including a thermometer, a surveying compass, a level, writing instruments, and even a mini globe. He also carried a small notebook made up of ivory leaves on which to record his observations. He would write down his measurements in pencil and in the evening transfer the data to seven large notebooks, each devoted to a different subject. He would then erase the ivory plates, readying them for another day of scientific inquiry.

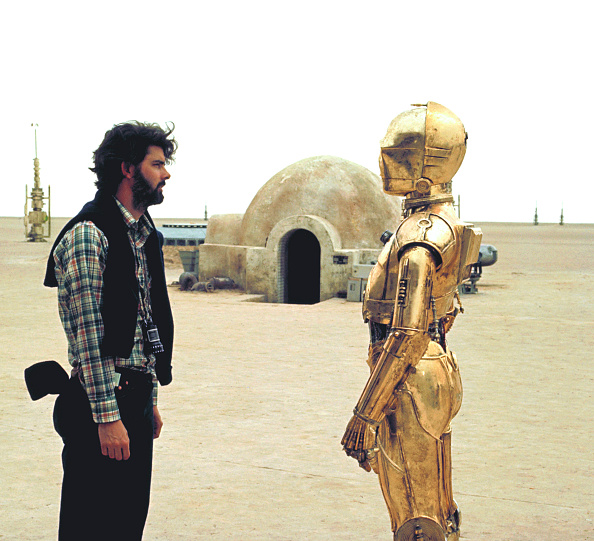

George Lucas

George Lucas

While working on a draft for Stars Wars, director George Lucas confined himself for 8 hours a day in his writing room, only knocking off for Walter Cronkite’s Evening News. But he also carried a pocket notebook with him at all times for taking down ideas, words, and plot angles on the go.

While mixing the sound for American Graffiti with Walter Murch, Murch asked Lucas for R2, D2, meaning Reel 2, Dialogue 2. Lucas liked the sound of that phrase and jotted it down in his notebook. This little note would of course come in handy later for the naming of that now famous robot. Names like Jawa and Wookie also began as quick scribbles in Lucas’ notebook.

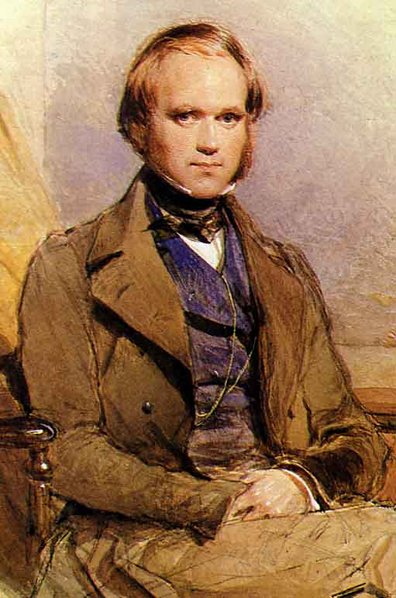

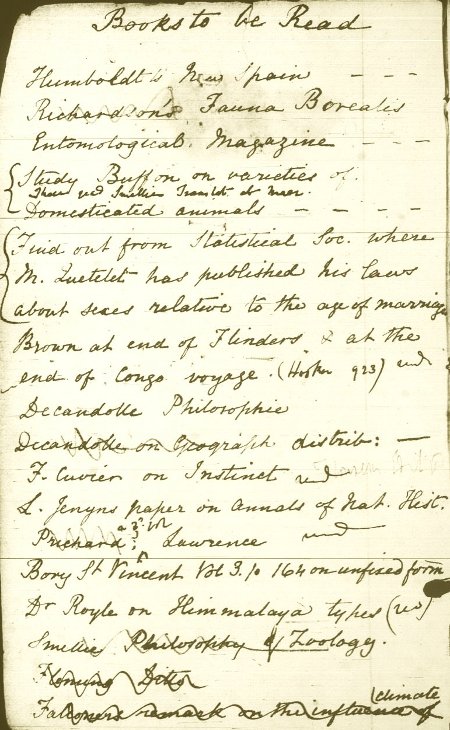

Charles Darwin

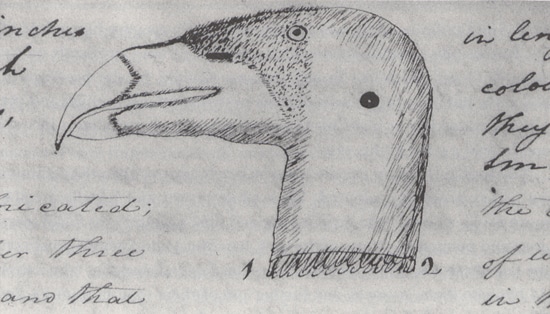

Charles Darwin began his pocket notebook habit while sailing as a naturalist aboard the HMS Beagle. While exploring the South American coast, he gathered specimens and filled 15 field notebooks with observations on subjects like zoology, botany, archeology, and linguistics, data like latitude and longitude, barometer readings, temperature, and depth soundings, sketches of maps and specimens, and personal information like diary entries, shopping lists, and financial information.

Charles Darwin began his pocket notebook habit while sailing as a naturalist aboard the HMS Beagle. While exploring the South American coast, he gathered specimens and filled 15 field notebooks with observations on subjects like zoology, botany, archeology, and linguistics, data like latitude and longitude, barometer readings, temperature, and depth soundings, sketches of maps and specimens, and personal information like diary entries, shopping lists, and financial information.

In Notebook B, Darwin began to speculate on the origin of species, here drawing his first evolutionary tree.

Near the end of the voyage he began writing in his Red Notebook, which he devoted to more theoretical speculations. Upon his return, he continued hashing out his theories in a series of notebooks he labeled with letters of the alphabet: A,B,C, D and so on. The notebooks were filled with memorandum to himself on things to look further into, questions he wanted to answer, scientific speculations, notes on the many books he was currently reading, natural observations, sketches, and lists of the books he had read and wanted to read. The notebooks provide a window into how Darwin’s theory of the transmutation of species, well, evolved. But the progression is far from orderly-the entries are chaotically arranged and wide-ranging; they jump from one scientific subject to the next and are interspersed with notes on correspondences and conversations.

When traveling and making field notes, Darwin would write vertically down the page with a pencil as this is easiest when holding the book in one hand and writing with the other. At home in his man room, he would rest the notebook on his desk and write horizontally down the page with a pen. And like Isaac Newton, he would sometimes start in from both ends of the notebook at once and work towards the middle.

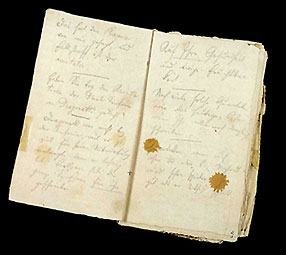

Ludwig van Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven was a devotee of the pocket notebook and was seldom seen without one in hand or pocket. He would walk the city streets and forest paths with it clutched behind his back in case inspiration should come upon him while away from home. His notebook became a memorable part of his appearance and artists who depicted him often included it in their images.

He used his notebooks to write down personal thoughts, maxims, and passages from literature and poetry he wished to remember. But their key use were as musical sketchbooks, where he would compose the beginnings of symphonies and then tinker with them in page after page. He believed that writing stimulated his imagination and even at home he kept a small table by his piano where he would hash out his creations on paper.

His notes and sketches were indecipherable to his associates. Wilhelm Von Lenz wrote in 1855, “When Beethoven was enjoying a beer he might suddenly pull out his notebook and write something in it. ‘Something just occurred to me,’ he would say, sticking it back into his pocket. The ideas that he tossed off separately, with only a few lines and points and without barlines, are hieroglyphics that no one can decipher. Thus in these tiny notebooks he concealed a treasure of ideas.”

Later in life, the notebooks served a more practical purpose-as a means of communication. Because of Beethoven’s hearing loss, his friends would use conversation books to write down what they wished to say to Beethoven, and he would respond orally or in the book as well.

Conversation book

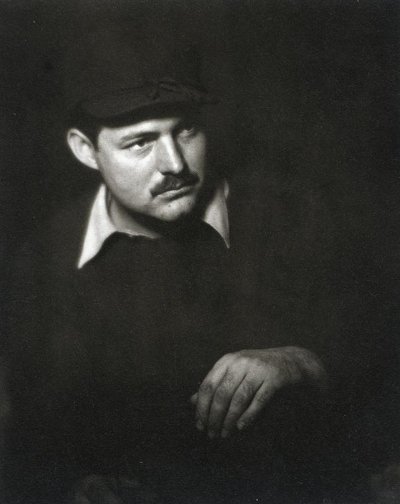

Ernest Hemingway

“The blue-backed notebooks, the two pencils and the pencil sharpener ( a pocket knife was too wasteful), the marble-topped tables, the smell of cafe cremes, the smell of early morning sweeping out and mopping and luck were all you needed.” –The Moveable Feast

One of Hemingway’s first notebooks. Made in 1908 while he was in elementary school. “I intend to travel and write.”

There has hardly been a more passionate devotee of the pocket notebook than Ernest Hemingway. “I belong to this notebook and this pencil,” he declared. The writer filled notebook after notebook, famously penning new story ideas in the cafes of Paris. He would sit there most of the day, waiting for inspiration to strike:

“I would stand and look out over the roofs of Paris and think, ‘Do not worry. You have always written before and you will write now. All you have to do is write one true sentence that you know.’ So finally I would write one true sentence, and then go on from there. It was easy then because there was always one true sentence that I knew or had seen or had heard someone say.”

But Hemingway’s notebooks didn’t just come out at the cafes; he brought them on all his travels and adventures, jotting down notes wherever he was-a bar, a train, a bullfight. He was a keen observer of life, trying to capture the richness and texture of his experiences. He stored sights, sounds, and smells away for future use when they would reemerge as vivid passages in his short stories and novels.

Of course the notebooks were not just for literary purposes-he used them to record expenses, make lists of gifts he wanted to bring back to loved ones from his travels, and even to keep track of his first wife’s menstrual cycles.

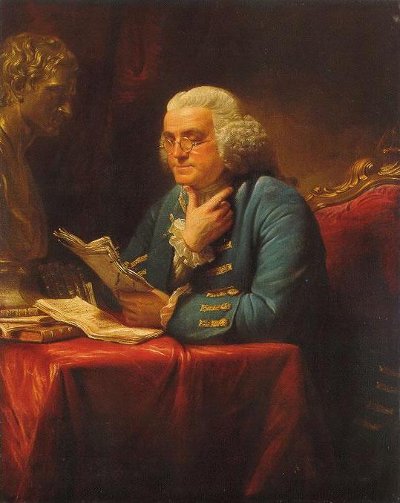

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin, being the singular man that he was, used his pocket notebook for a singular purpose. At the age of 20, Franklin decided to seek the lofty goal of moral perfection. In order to accomplish his goal, Franklin developed and committed himself to a personal improvement program that consisted of living 13 virtues.

In order to keep track of his adherence to these virtues, Franklin made 13 charts in a small notebook he carried with him. The charts consisted of a column for each day of the week and 13 rows marked with the first letter of his 13 virtues. Franklin evaluated himself at the end of every day by placing a dot next to each virtue he had violated. The goal was to minimize the number of marks, thus indicating a “clean” life free of vice.

Franklin would especially focus on one virtue each week by placing that virtue at the top of that week’s chart. Thus, after 13 weeks he had moved through all 13 virtues and would then start the process over again. Initially, he erased the marks to reuse the notebook, but after doing this many times, it started to make holes in the paper. So he then switched to keeping the charts in a memorandum book made with ivory leaves that could be wiped clean and reused over and over again.

Franklin did several courses of his program in a year, then one course a year, and then one every several years, before finally becoming too busy with other matters to keep it up. “But I always carried my little book with me,” he said. Indeed, he was so proud of this project that even 50 years later while living in France he would take out his ivory tablets to show acquaintances. The notebook was imbued with a bit of mystique; a French friend recalled he was thrilled to have touched “this precious booklet.”

While Ben never attained moral perfection, he felt the project did help him become a better man. When he was 79 years old, Franklin wrote, “I am indebted to my notebook for the happiness of my whole life.”

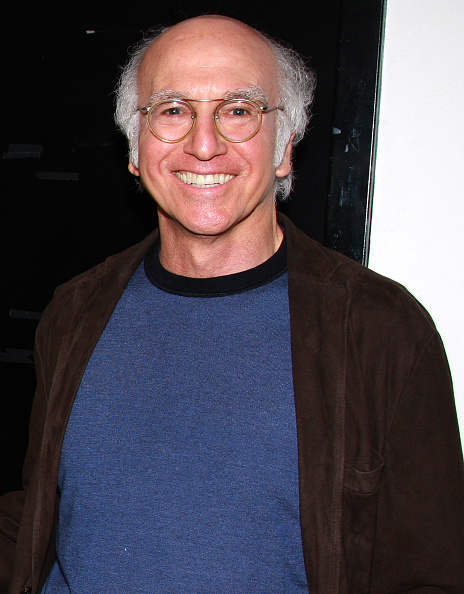

Larry David

Many comedians carry around a little notebook in order to jot down funny thoughts or observations that might come in handy later. Larry David is particularly devoted to this practice. He always keeps a small notebook in his breast pocket. When he worked on Seinfeld, he would scour his notebook for ideas for the show; episodes like “The Contest” came right out of it.

The notebook continues to provide fodder for his current show, Curb Your Enthusiasm, as described in this excerpt from a New Yorker article:

“Like many comedians, Larry David carries a pocket notebook for writing down ideas. ‘You’re in a parking garage, and Larry’s wallet is empty–he forgot to ask his assistant to go to the cash machine,’ [Robert] Weide, who directs several episodes a year, says. ‘So he says, ‘Shit, I have no money for the valet–could you give me a few bucks?’ So you find yourself giving money to Larry David, who has a few bucks. And then out comes the little notebook.’

‘What would I have done if he hadn’t been there?’ David said. ‘That could have been funny.’

The notebook is a ratty brown thing that looks as if it might have cost forty-nine cents at a stationery store. Its pages are covered with David’s illegible scrawl.”

The notebook even makes appearances in the show itself. In one episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm (which depicts a fictionalized version of David’s life), he leaves his notebook at the neighbors’ house, and when they bring it over, they ask for the $500 reward David had promised inside the front cover to anyone who returned the lost notebook. “Let me get you a check, Sherlock,” David seethes off screen.

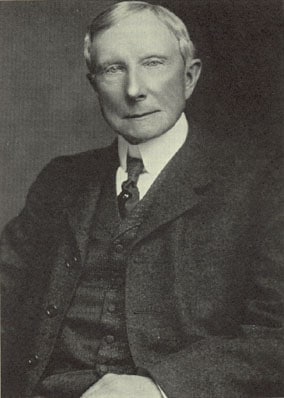

John D. Rockefeller

John D. Rockefeller’s zeal for detailed bookkeeping was legendary. He loved to meticulously pore over his ledger books and took great pleasure in having every fact and figure right at his fingertips. And he was constantly trying to figure out ways to make his business more efficient; he was never satisfied with the status quo. His aid in this efficiency crusade was a little red notebook he always kept with him in which he would jot down notes to himself, along with facts, figures, and calculations.

Rockefeller took his notebook on tours of his refineries and processing plants. He carefully observed the plants and probed the managers with a myriad of questions as he made notes of ways things could be improved. And he always followed up on these ideas. Thus the little red notebook had the power to strike a bit of fear in his underlings. “More than once I have gone to luncheon with a number of our heads of departments and have seen the sweat start out on the foreheads of some of them when that little red notebook was pulled out,” Rockefeller remembered with enjoyment.

Rockefeller understood that a penny saved somewhere along the line could snowball into a hefty sum. For example, while touring a plant he saw that 40 drops of solder were being used to seal kerosene cans destined for export. He asked the foreman to try sealing them with 38 drops; some leaked with 38, but none with 39, and so the switch was made. Rockefeller recalled, “That one drop of solder saved $2,500 the first year: but the export business kept on increasing after that and doubled, quadrupled-became immensely greater than it was then: and the saving has gone steadily along, one drop on each can, and has amounted since to many hundreds of thousands of dollars.”

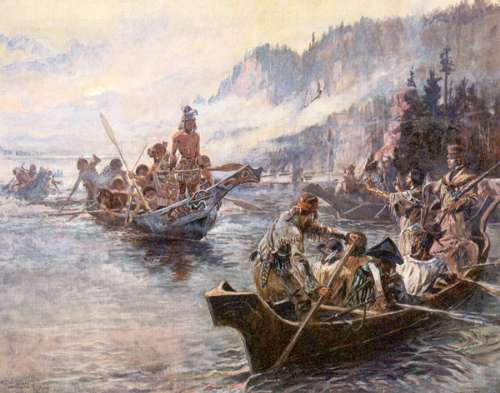

Lewis and Clark

With the 1803 Louisiana Purchase, the United States acquired nearly a million square miles of territory, territory that had yet to be officially mapped and explored. Americans knew very little about this new swath of their country, and Jefferson charged the Corps of Discovery with finding out just what was out there. Jefferson was not only interested in the men finding river routes to the Pacific, but as an amateur naturalist and scientist himself, was also extremely keen on discovering just what geography, climate, plants, peoples, and animals inhabited this frontier. So he charged the expedition with recording a long list of information, from the lay of the land to the disposition of the native peoples they encountered. He asked them to keep multiple journals and to take extremely good care of them.

With the 1803 Louisiana Purchase, the United States acquired nearly a million square miles of territory, territory that had yet to be officially mapped and explored. Americans knew very little about this new swath of their country, and Jefferson charged the Corps of Discovery with finding out just what was out there. Jefferson was not only interested in the men finding river routes to the Pacific, but as an amateur naturalist and scientist himself, was also extremely keen on discovering just what geography, climate, plants, peoples, and animals inhabited this frontier. So he charged the expedition with recording a long list of information, from the lay of the land to the disposition of the native peoples they encountered. He asked them to keep multiple journals and to take extremely good care of them.

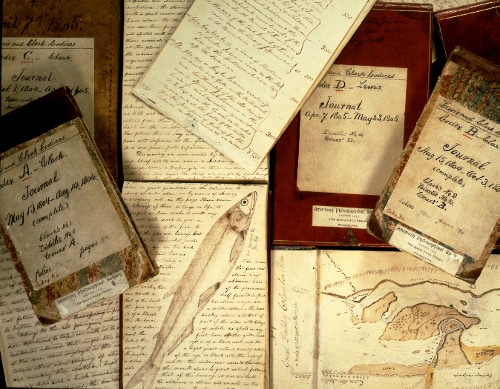

The Corps of Discovery carried out this order with all due diligence. Not only did Captains Lewis and Clark keep notebooks on their observations, but the other soldiers did as well, producing in all more than one million words during their travels.

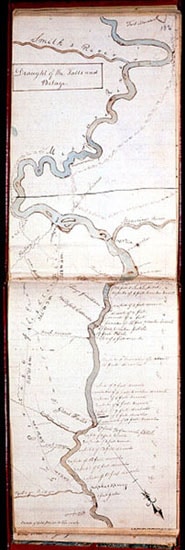

Lewis and Clark kept 18 of what Jefferson called their “traveling pocket journals;” 13 were larger notebooks bound in red morocco leather, 4 were smaller and bound in paper board, and one was Clark’s field notebook bound in elkskin. Clark carried this elkskin field book during times of inclement weather or while canoeing down a river in order not to risk damage to one of the larger red notebooks. He would then copy his field notes into the red notebooks later on. When all the notebooks were not in use they were kept protected in tin cases. When their pages had been completely filled, the notebooks were sealed safely shut inside the cases for a safe return to Washington.

Shoshone smoking pipe

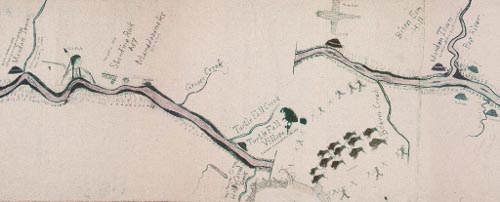

Falls and portage of the Missouri River.

Historian Donald Jackson called Lewis and Clark “the writingest explorers of their time.” The men “wrote constantly and abundantly, afloat and ashore, legibly and illegibly, and always with an urgent sense of purpose.” Their journals covered astronomy, weather, natural history, botany, animals, anthropology, maps, and much more, and today offer an incomparable snapshot of the frontier of America.

George C. Marshall

George C. Marshall always kept a small notebook with him, and it would bear rich fruit during his tenure as the U.S. Army Chief of Staff during WWII.

Between the World Wars, Marshall served as aide-de-camp to General Pershing, worked within the War Department, commanded the 15th Infantry Regiment, and taught at the Army War College. These positions brought him into contact with many up and coming officers admist the Army’s ranks. Wherever he went, he carefully observed the men he met and encountered. He would jot down the names of those he considered promising candidates for future leadership positions, making notes of the men’s strengths and particular characteristics. The names of men like Patton, Eisenhower, Bradley, and Stilwell could be found on the pages of his famous notebook.

When WWII broke out, Marshall didn’t want over-the-hill generals ordering young men into battle; instead, he looked for leaders who, even if controversial, could be dynamic in their thinking and strategy. To find the men ready for top commands, Marshall had to simply flip open his notebook and look over his notes. He became known for having a “gift” for putting the right people in the right positions. But it was a gift born of preparation…and a pocket notebook.

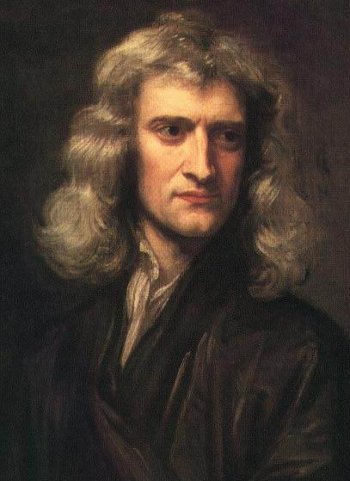

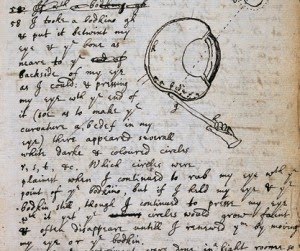

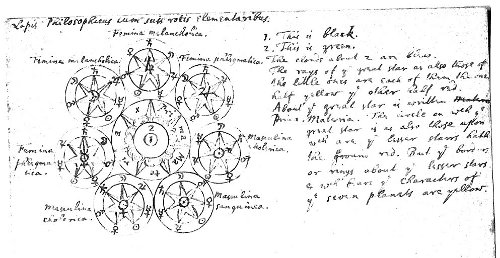

Isaac Newton

Isaac Newton began his habit of keeping a notebook as a boy-he would write out lists of words and recipes for things like colored dyes. But his notebook keeping began in earnest when he arrived at Cambridge as an undergraduate. In the 17th century, students were encourage to keep a large “commonplace book” in which they recorded all their notes and acquired knowledge. But on the advice of his Cambridge tutor, Newton instead started a set of small notebooks, each dedicated to a specific subject-theology, mathematics, chemistry, and philosophy. Newton’s method of inquiry was to pose a question, study and analyze all the evidence, and record his deductions in his notebooks.

Newton had an obsession for organizing and categorizing information, and he would typically lay out his notebooks by listing the subjects he wished to study throughout the book and then entering notes under the headings as he learned and gathered new knowledge. He would also start in on both ends of the notebook at once, covering different subjects on each end and numbering the front half with Roman numerals and the end half with Arabic numerals. He would then return later to fill in the blank middle section with a different subject.

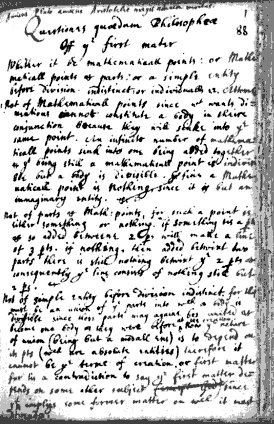

Newton’s philosophical notebook is particularly prized among scholars for its insight into Newton’s intellectual development. Inspired by the philosophy of Rene Descartes, he endeavored to explore all the quaestiones quaedam philosophicae (Philosophical Questions). He made 45 different headings in his notebook on topics ranging from atoms and color to God and the soul.

First page of the Quaestiones.

He organized his theological notebook in the same way, making a list of headings on various theological subjects at each end of the notebook. The front part was used to systematically study the Bible and record what it said about each subject; the end of the notebook was used to further explore the questions which had been raised during this scripture reading by seeing what the church fathers had to say on the topic. He even wrote up an index to this book so that he could reference the entries and insights he had gained throughout his life.

For the rest of his life, Newton not only returned to his old notebooks but filled many dozens more with insights and experiments in everything from alchemy to mathematics.

Notebook entry on alchemy

Frank Capra

In his autobiography, Frank Capra recalls how, without any real previous experience, he stumbled into being asked to direct his first short film, The Ballad of Fultah Fisher’s Boarding House, based on a poem by Rudyard Kipling. Worried about failing, Capra prepared as much as possible, with help from his pocket notebook:

“Came the morning of ‘shooting.’ The saloon looked perfect, foggy with smoke as I ordered, and smelly with beer on the sawdust. The ‘actors,’ standing around in open-mouthed wonderment, were so villainous Kipling would have loved them. I had every scene in my mind and sketched out in a pocket notebook; long shots, near shots, face shots-all in chronological order. A pomaded Montague gripped my hand, wishing me luck.”

Pablo Picasso

Picasso utilized his pocket notebooks to make preliminary sketches before he began a painting. This was particualrly true in the case of preparing to paint what would become Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Driven by his artistic passion and an intense rivalry with Henri Matisse, Picasso made 809 sketches for the painting in many notebooks over a period of nearly six months-more preparatory sketches than for any other known artwork in history.

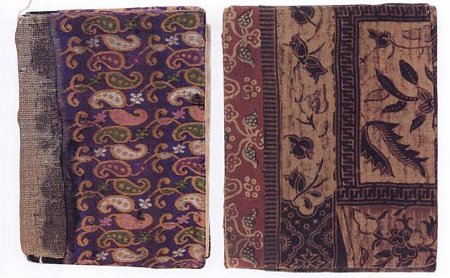

Picasso thought so much of his notebooks that he wrapped some of them with pieces of colorful fabric. Others he painted with stars, zig zags, stripes, and dots.

Prepatory sketch for ‘Guernica’

His notebooks were indispensable to his art, but they also kept him sane during trying times.

From 1932-1935, two books which exposed Picasso’s private life were published, his mistress gave birth to his child, and his wife left him and took their son with her. Picasso called this period “the worst time in my life.” Hoping to strip his life back to the essentials, he confined himself in near isolation in Paris. But as his friend Jaime Sabartes recalled, his trusty pocket notebook remained his companion:

“Picasso was endeavoring to recapture the simplicity of our life as young men, despite the manifold and profound changes in us and around us. He wanted to return to a bygone period in our lives. He neither painted nor sketched and never went up to his studio except when it was absolutely necessary, and even then he put it off from day to day, no matter how urgent. In order to occupy his imagination, he wrote-with a pen if he found one handy, or a small stub of pencil-in a little notebook which he carried about with him in his pocket. He wrote everywhere.”

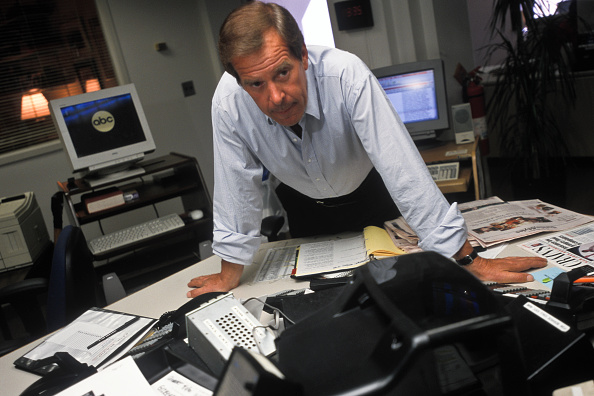

Peter Jennings

To go from a high school dropout to a respected foreign correspondent and news anchor takes hard work and attention to detail. Peter Jennings particularly set himself apart from other journalists with his zeal for the latter. Vice President and Managing Editor of News for ABC, Paul Friedman, remembered:

“Whenever we would go out on a story he carried a reporter’s notebook around with him-a small spiral notebook that he used to put in the back of his pants, inside the belt. He would take incredibly detailed notes. So if you went anywhere in the world, he would go back to his file of spiral notebooks and you’d hit the ground running because he could say, ‘well, there is this guy I talked to last time. Here is his telephone number and we’ll call him.’ All reporters do that, but Peter did it in incredible detail.

I remember going to Cuba with Peter on a story. We needed a sugarcane field for a standup, talking about the economy. Peter looked in one of his notebooks and he looked around and said, ‘If you go down that road about a mile, there’ll be a church on the left. Hang a left at that church, drive a little while after that, and there will be a sugarcane field.’ Sure enough, there it was.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Emerson was surely one of the most prolific notebook-keepers in history. He kept 263 notebooks on a variety of subjects and for a variety of purposes. His notebook collection became so unwieldy, it required a 400 page index to help Emerson find what he was looking for. And then he made indexes for specific subjects too and an index just for references to people in his notebooks-839 in all. He even had indexes for his indexes.

What did Emerson write in all of these journals and notebooks? Perhaps it would be easier to make a list of what he did not write down. His larger journals were filled with notes on his prodigious reading (he kept four small notebooks just to list the books he had read), philosophical musings, excerpts of letters, recollections of dreams, and translations of ancient and modern writings. He kept a series of topical notebooks, each devoted to a different subject: Beauty and Art, Reality and Illusion, Country Life, Rhetoric, and Notes on Love.

There were notebooks devoted to his lectures and notebooks devoted to observations and memories of people in his life like Henry David Thoreau. He kept 30 pocket-size diaries to record daily happenings. Other pocket-size notebooks were given specific purposes: drafts of poems and lectures, notes on his trees and garden, and a collection of quotes which he kept on hand to supplement his writings, sermons, and lectures. When he used a quote he would mark a line through it to indicate such. On his traveling lecture tours he brought small leather bound pocket notebooks which he used to keep track of his expenses and to make observations about the sites, local peoples, economy, and geography of the places he visited. In short, Emerson was simply always writing-nature, religion, politics, people, culture-it all drove him to put pen to paper.

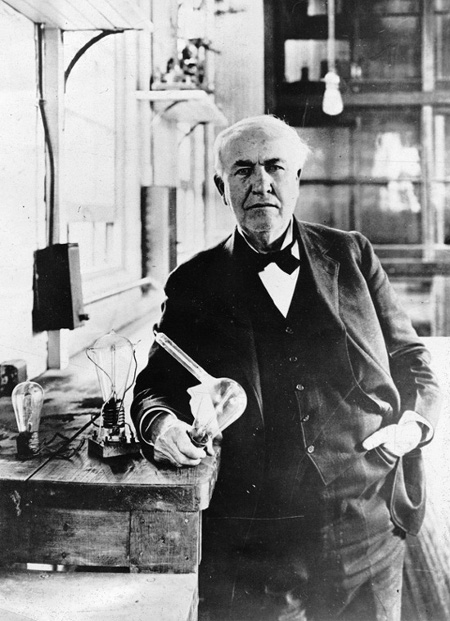

Thomas Edison

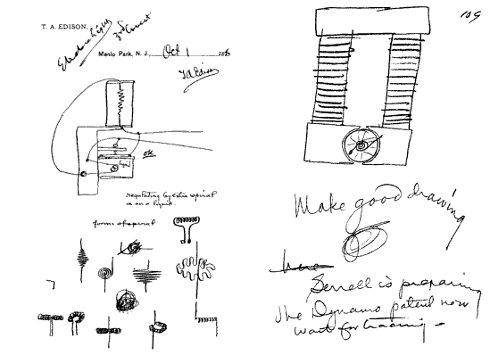

Thomas Edison started using a pocket notebook as a teenager. He carried it wherever he went and used the notebook to make observations about the natural world, jot down bits of inspiration, record the results of experiments, and draw diagrams and pictures of new ideas. He continued this practice as an adult.

On the advice of a patent attorney, he also kept a set of notebooks specifically for officially recording his ideas in case he had to defend their origin in court.

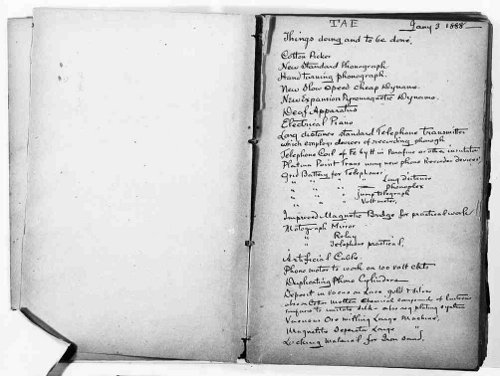

In 1888 he started a notebook entitled “Private Idea Book.” Within its pages Edison wrote down ideas for inventions he planned to bring to fruition in the near future. These inventions included “artificial silk,” “platinum wire ice cutting machine,” “electrical piano,” “toy phonograph for dolls,” and perhaps most curiously, “ink for blind:”

Edison’s To-Do List

Edison also personally vetted each piece of music his company recorded and released and kept a set of notebooks full of his reasons for giving songs the thumbs up or thumbs down.

Edison ordered the staff at his famous Menlo Park laboratory to adopt his avid notebook-keeping habit, and he and his associates generated 2,500 pocket notebooks of 200-250 pages each during his lifetime.

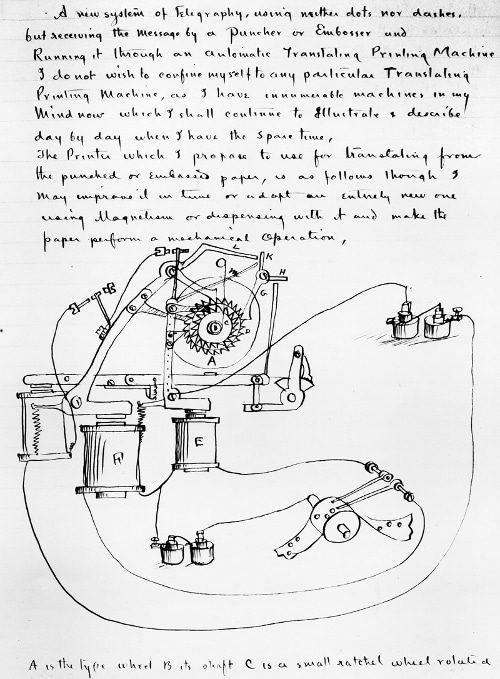

August 31, 1871 notebook entry for an Automatic Translating Printing Machine for Telegraphy

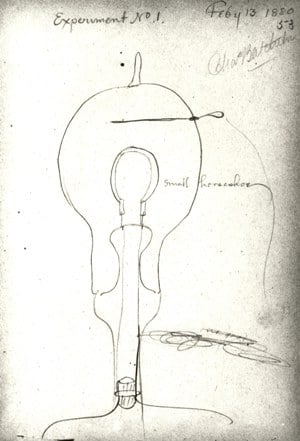

Early sketch of Edison’s incandescent light bulb.

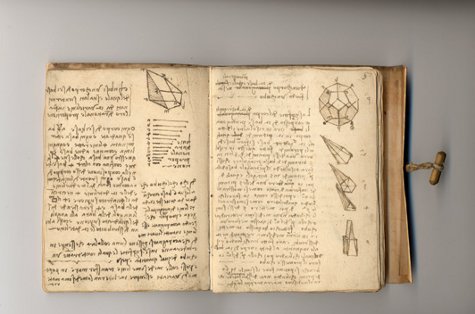

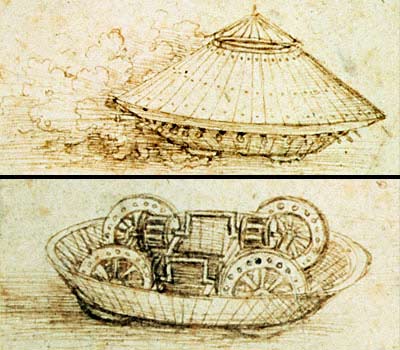

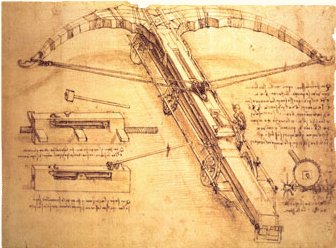

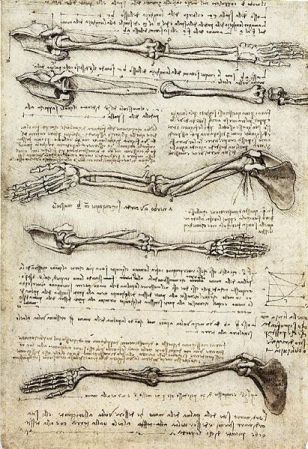

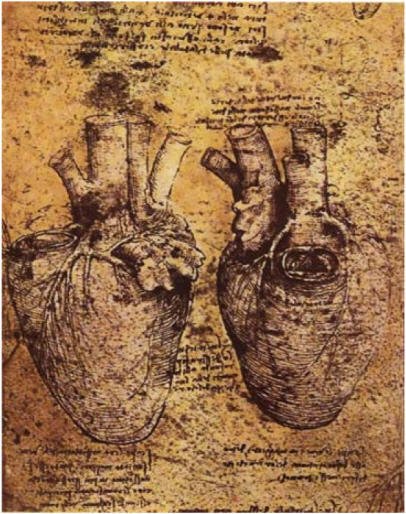

Leonardo da Vinci

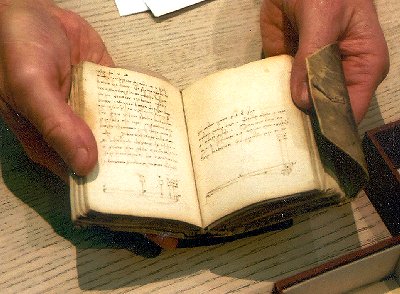

Like Emerson, Leonardo da Vinci was a positively prolific writer. 13,000 pages of his writings have come down to us, and there may be another 10,000 which have gone missing. He frequently wrote on loose sheets of paper that he kept barely organized; he made his own “notebooks” by folding the sheets and wrapping them in fabric. But when he turned thirty he also began writing in leather-bound journals. And he carried small bound notebooks with him at all times. He kept these tiny 3.5X2.5 notebooks tied to his belt, always at the ready for his thoughts, observations, drawings, and ideas.

Leonardo has been called “the most curious man who ever lived.” He was always asking questions and thinking of new things to investigate. His notebooks are filled with musings and drawings on every conceivable subject: philosophy, art, botany, geology, anatomy, flight, water and many more. His tireless mind flitted from one idea to the next; on the same page of his notebook he might wax poetic on the human form, sketch a plant, start a draft of a letter, and even record his expenditures and that night’s dinner menu.

The sudden jumps from topic to topic, even within a single page, are not the only thing that makes Leonardo’s notes hard to decipher. He famously wrote in “mirror writing” from right to left across the page, although not because he was trying to keep the writings secret; as a left hander it was simply a way to keep the ink from smearing as he wrote. His writing also lacks punctuation, and he was apt to combine several short words into one long one or divide long words into smaller parts. But while the chaos of his notebooks may impede the average person from delving into their contents, the profound mish-mash only adds to the man’s mystique and mystery and our fascination with his legendary mind.

Listen to our podcast on the field notebooks of Theodore Roosevelt: