This article series is now available as a professionally formatted, distraction free ebook to read offline at your leisure. Click here to buy.

If you’ve been following along with our resiliency series, you probably know by now that it’s much easier to read and understand these principles than it is to incorporate them into your life. Much of how you think and cope with challenges solidified way back when you were a kid and thus transforming those thinking patterns now is a difficult task.

While you can’t go back and change your childhood, you can play a huge role in shaping the resiliency of your children and give them this vital leg up in life. A resilient spirit is one of the greatest gifts you can give your kids. It is a skill that will help them do better in school and work, have healthier relationships, and live a happier, and maybe even longer life. It’s the key to helping them reach their potential: while talent is important, studies have shown that optimistic kids will rise above their potential while pessimistic kids will fall below it.

In this last part of our resiliency series, we will review some of the principles we have previously discussed, talk about how they apply to children, and outline some additional things that educators and parents need to know about boosting kids’ resiliency. But first, let’s talk about what’s handicapping the resiliency of today’s generation of children.

The Self-Esteem Movement and the Weakening of Children’s Resiliency

There’s no shortage of hand wringing these days about the coddling of kids and the dangers of overzealous “helicopter parents.” This concern over kids “getting soft” is easy for some to dismiss as just another spin on an age old criticism leveled by each and every generation (“Back in my day Sonny…”).

But the worry that today’s kids are coddled-overpraised and underworked-is not without legitimacy. The adoption of the “self-esteem movement” into school curriculum has been well-documented, and its negative effect on kids’ resiliency has been studied and proven by psychologists.

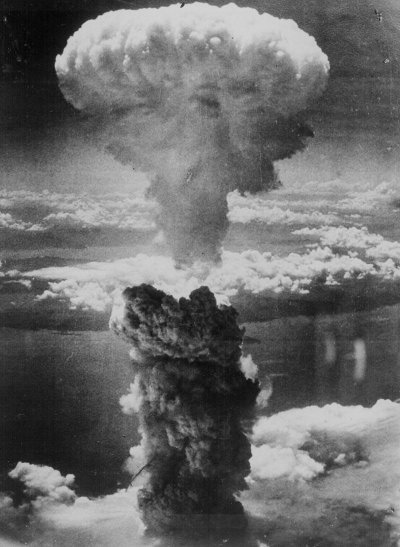

The “self-esteem movement” took off in the 1960s. With the Depression and World War behind us and the economy booming, an emphasis on human choice emerged, not just in the marketplace, but in the cultural ideal that each individual was able to shape his or her personality and destiny. The greater one’s sense of self, the happier the self, the farther you’d go.

In 1969, psychologist Nathaniel Brandon published a very influential paper called “The Psychology of Self-Esteem” in which he argued that “feelings of self-esteem were the key to success in life.” Brandon’s ideas were first institutionalized when a task force, charged by the California state legislature, formulated a set of recommendations entitled, “Toward a State of Esteem.” The report argued that low self-esteem caused a variety of ills from academic failure to teen pregnancy and that teaching self-esteem in schools would be a “social vaccine” to inoculate kids from these problems. It recommended that every school district in California strive for the “the promotion of self-esteem…as a clearly stated goal, integrated into its total curriculum and informing all of its polices and operations” and that “course work in self-esteem should be required for credentials..for all educators.”

Other states and schools were swept up into the self-esteem movement and incorporated self-esteem boosting exercises into their curriculum and programs. These exercises were designed to make students feel good about themselves, under the belief that these good feelings would then beget all sorts of success for the students.

However, true self-esteem actually has two components-feeling good and doing well. And the self-esteem movement got their order mixed up. While the California report posited that low self-esteem causes problems like teen pregnancy and welfare dependence, studies have shown that the opposite is true; low self-esteem is the consequence, not the cause, of such behavior. Thus you can’t start with the “feeling good” and have it lead to doing well. It happens the other way around. Feeling good, and true self-esteem, naturally follow from doing well. You can’t pump kids full of self-esteem-it’s something they have to earn for themselves.

By sticking the cart before the horse, the well-meaning self-esteem movement has actually hurt children’s self-worth and resiliency. Dr. Martin Seligman, who has studied the issue extensively, argues:

“By emphasizing how a child feels, at the expense of what the child does-mastery, persistence, overcoming frustration and boredom, and meeting challenge-parents and teachers are making this generation of children more vulnerable to depression.”

Seligman points out the irony that during the period we’ve been focused most intently on boosting kids’ self-esteem, levels of childhood sadness, pessimism, and depression have risen to unprecedented levels. We’re clearly tackling the problem the wrong way.

If educators and parents truly want to boost their children’s self-esteem, then the key is to teach kids the life skills and principles they need to be successful, and the self-esteem will naturally follow from their accomplishments. Let’s discuss some of the ways this can be done.

The Origins of Children’s Explanatory Style

As we explained in Part II, your explanatory style is how you typically explain the events that happen to you. When faced with setbacks, pessimistic people fall into a Me/Always/Everything style. Their problems are always their fault and are permanent and pervasive. Optimistic people explain bad events with a Not Me/Not Always/Not Everything approach.

Kids as young as eight have already developed their explanatory style. What factors shape how they explain the world and what happens to them? There are three factors.

Their parents’ explanatory style. Explanatory style is not genetic, but it does gets passed down in a big way. Kids have a lot of “why” questions and they listen intently to the things their parents say to figure out the answers and how the world works. If you’re constantly using a Me/Always/Everything approach, your kids are going to adopt it.

Mom is actually the one who has by far the biggest effect on her children’s explanatory style. A child with a pessimistic mom will very likely turn into a pessimistic adult. This is because of the amount of time mom spends with her kids each day; if you’re a stay-at-home dad, then you’re the one they’re watching.

Teachers’ and parents’ criticism. How a parent or teacher criticizes a child can have a big effect on his or her explanatory style. Adults cultivate a pessimistic explanatory style when they tell children that their problems are permanent and pervasive instead of temporary and specific. This is the difference between a teacher telling a student he failed a test because “You didn’t study hard enough” versus “You’re just not good at math.”

Interestingly, girls tend to hear more permanent and pervasive criticism from their teachers than boys do. Girls typically behave in class while boys are more rowdy; thus, when a boy makes a mistake, the teacher chalks it up to him not paying attention; when a girl makes a mistake, the teacher is left saying something like, “I guess you just aren’t motivated to learn.” Dr. Seligman posits that this early training may be why women suffer more depression later in life than men; they develop a pessimistic explanatory style as a child and carry it into adulthood.

Environment/Crisis in Upbringing. Factors like a chaotic upbringing, seemingly unchangeable poverty, and the loss of a parent, ingrain in children that bad events are permanent and pervasive, an idea they can carry over to all setbacks they experience.

Shaping an Optimistic Explanatory Style

So if your kids are learning their explanatory style from you (sobering, right?), what can you do to help them think more optimistcally?

Of course, the number one thing is to model a positive style yourself. Your kid is watching you all the time. Additionally-

Criticize behavior, not character. Holding your kid accountable for what they do is crucial, but how you go about it is very important. Criticism of children’s character, of their self, teaches them that their problem or fault is permanent and pervasive. This breeds passivity as the child will feel like there’s nothing he or she can do to change. But criticizing behavior teaches them that the problem is temporary and limited in nature; it’s solvable and something they can work to change and overcome.

Dr. Seligman provides these examples to illustrate the difference between criticizing character versus behavior:

- “Tammy, what’s wrong with you? You are always such a monster!” vs. “Tammy you are really misbehaving today. I don’t like it at all.”

- “You are a bad boy.” vs. “You tease your sister too much.”

- “She never likes to play with other kids. She’s so shy.” vs. “She has a hard time joining groups of kids.”

- “You are not athletic.” vs. “You have to work harder to keep your eye on watching the ball meet the bat.”

- “You kids are so selfish.” vs. “You kids must share more.”

- “Another C-minus? I guess you just aren’t an A student.” vs. “Another C-minus? You need to spend more time on your studies.”

- “This room is a pig sty! You are such a slob!” vs. “This room is a pig sty. You need to start picking up after yourself.”

PS-What goes for how you criticize your kid, carries over to how your criticize your spouse. Remember, your child is watching and modeling your behavior.

Teach your children their ABC’s. In Part II we talked about the ABC’s of resiliency. A is for adversity, B is for beliefs, and C is for consequences. It’s not the adversities themselves that create consequences, but our beliefs about those adversities. This is a crucial thing to teach your kids. Parents often concentrate on the A and the C-asking their kids what happened and how they are feeling. But they also need to help their children discover the beliefs behind their feelings. Ask them questions about why they’re feeling the way they are and help them see how their B’s have led to their C’s.

Teach your children how to dispute their negative thoughts. If your child’s beliefs about their adversities are inaccurate and overly negative, help him or her to generate alternatives to how they’re currently viewing things. Tell them to act like a detective gathering evidence for and against their interpretation of what is going on. Encourage them to look at the issue from different angles and put themselves in the other person’s shoes. If they’re catastrophizing, take them through the exercise outlined in Part VI.

Let Them Fail

When parents see their kids hurting, whether physically or emotionally, the natural tendency is to swoop in and make them feel better, to take the pain away.

By and large this is a normal and healthy impulse; children are vulnerable and need their parents to care for and protect them.

But pain also serves a valuable purpose in every person’s life, both young and old. It teaches us about things to avoid, shows us when we’ve made mistakes, and shapes our future behavior. Pain can be a teacher and without it we can’t progress.

Thus the parental impulse to stop all of a child’s hurt can be misplaced and can actually stand in the way of a child’s growth and the building of their resiliency. Solving all of your children’s problems takes away their pain in the short term, but impedes their ultimate happiness.

Children need to try things on their own, fail at them, and experience negative emotions like sadness and frustration. They need to learn to persist in the face of failure. Without failure and persistence, there’s no mastery (the feeling of being in control and knowing that taking certain actions get specific results). And without mastery, there’s no self-esteem and no resiliency.

Give Unconditional Love and Conditional Praise

At the same time that the self-esteem movement was taking off, the idea of “unconditional positive regard” was also entering the public consciousness. Coined by Carl Rogers, it’s the idea that complete acceptance and support, no matter what a person did, constitutes the foundation of effective psychotherapy.

This term was popularized in the culture as “unconditional love,” a term quite familiar to us today, but one that outside of religious discourse was not common until the 60s. When it comes to kids, it’s an idea with some merit. When building your children’s resiliency, you want to encourage mastery and prevent helplessness. And creating a safe, loving environment is indeed an effective way to help your child learn mastery. For a child to feel secure in exploring and taking chances, he or she must feel safe. An environment of positive regard, free of fear, creates an atmosphere where a child feels confident in striking out and trying new things.

But unconditional positive regard can dissolve your child’s resiliency.

In Part II, we discussed the phenomena of learned helplessness. When dogs were given shocks that they couldn’t do anything to avoid, they learned helplessness, becoming passive and depressed even when given tasks they could control.

But learned helplessness is not just the result of uncontrollable negative events, it can also be caused by uncontrollable positive events. Dr. Seligman explains:

“Unconditional positive regard is just that-unconditional, that is, not contingent on anything your child does. This distinction cannot be glossed over. . . When a person or an animal receives good events noncontingently-nickels fall out of the slot machine regardless of what the person does, food that is delivered regardless of what the animal does, praise that rains down regardless of whether a child actually succeeded-learned helpless develops. . . Recipients of noncontigent good events do not become depressed like recipients of noncontigent bad events, but they do become passive and lethargic. Even worse, they have trouble learning that they are effective, seeing later on that their actions work, once they regain mastery. A rat, for example, that first learns it can get food regardless of what side of a maze it goes to has inordinate trouble later on learning to go to the correct side when food becomes available only on one side.”

When a child is rewarded and praised no matter what he does, he comes to see that positive attention is outside of his control and not contingent on good behavior or success. This saps his motivation to try and challenge himself. Additionally, when you praise kids enthusiastically for things they know they didn’t do well, the value of your praise diminishes. So if your kid struck out all season in little league and you keep saying, “You did so awesome out there!” The kid knows you’re lying, and the next time you praise him for something, even if you mean it, he’s not going to believe it. It erodes his trust in you.

So there seems to be a dilemma here: on the one hand creating positive regard boosts resiliency by giving children the safety to explore, while on the other hand, too much positive regard diminishes resiliency by teaching a child helplessness. The balance can be found in unconditionally providing your child with “love, affection, warmth, and ebullience,” but doling out praise conditionally. Praise your child when they have success, not simply to stop their hurt or make them feel better. Seligman also argues that you need to grade your praise, that is, let the praise fit the accomplishment-a little praise for putting one’s socks away, gushing praise for bringing home straight A’s.

In short, give unconditional love, and conditional rewards and praise.

Internal Locus of Control

In Part III, we discussed how important having an internal vs external locus of control is when it comes to resiliency. Much of our locus of control takes form in childhood. So how can you help your child feel less like a victim and more in control of his life?

A study done in 1967 by Stanley Coopersmith showed that parents who gave their kids the most rules and limits had children with the highest self-esteem, while those who gave their kids the most freedom had kids with the lowest self-esteem. Kids want limits, and they’re essential to their healthy progress.

Giving your child consistent limits, rewards, and discipline is one key in shaping an internal locus of control. People with an internal locus of control believe that by doing x, they can get z, they see a correlation between action and consequences. Consistent parenting ingrains these kinds of connections in your child’s mind. Good behavior leads to reward. Bad behavior leads to punishment. Promise a reward for an accomplishment, and give it to your child if and only if they attain it. Set a rule and punishment, and if the rule is broken, follow through on the exact punishment promised, every time.

In experiments with animals, when the animals were given a “safety signal,” a beep before a punishment was doled out, the animals were able to deal with the punishment. But when the punishments could come at any time, and were not proceeded by a signal, the animals became highly anxious and withdrawn. They had no control and no pattern to set their expectations by. So make sure child knows why you’re punishing him and be sure the punishment fits the crime. And try not to “lose it” on them when they haven’t really done anything wrong, and you’re just having a bad day.

Encourage Exploration and Curiosity

Finally, encouraging your child’s curiosity is one of the best things you can do for his or her resiliency. As we discussed in Part III, curious people are open-minded, they want to know more about the world and about other people. This curiosity strengthens their resiliency because it makes them excellent problem solvers and aces at inter-personal relationships.

So don’t stifle your kids’ curiosity, even if they’re annoying and peppering you with a slew of questions. Answer their questions and encourage them to learn more. Give them experiences, whether in travel, musuems, or the great outdoors that lets them explore to their hearts’ content. Give them toys that are more open-ended and require active, imaginative play. If you’re an educator, don’t pour knowledge into the kids you teach, but help them figure out things for themselves.

Listen to our podcast on giving your children the gift of failure:

Sources

The Optimistic Child by Dr. Martin Seligman

Resiliency Advantage by Dr. Al Siebert

The Resilience Factor by Dr. Karen Reivich and Dr. Andrew Shatte

______________________________________________________

We hope you’ve enjoyed the resiliency series and have learned some things you can apply to your life! Resiliency is absolutely vital to your health and happiness. It’s a fascinating subject and there’s even more to learn than what we’ve presented here. If you’d like to know more, check out the sources we’ve used in the various articles. And here’s to facing the world with boldness, with courage, and with true resiliency!

_______________

Building Your Resiliency: Part I – An Introduction

Building Your Resiliency: Part II – Avoiding Learned Helplessness and Changing Your Explanatory Style

Building Your Resiliency: Part III – Taking Control of Your Life

Building Your Resiliency: Part IV – Iceberg Ahead!

Building Your Resiliency: Part V – Recognizing and Utilizing Your Signature Strengths

Building Your Resiliency: Part VI – Quit Catastrophizing

Building Your Resiliency: Part VII – Building Your Children’s Resiliency