Every boy dreams of being a superhero, and knows that donning a cape or Spiderman costume is hardly just for Halloween.

But as we get older, we realize we don’t possess the supernatural powers of Spidey (or Batman’s primo cache of gadgets). And we notice the absence of the kind of otherwordly arch nemeses that plague our comic book heroes in the real world. The idea of being a hero is gradually put aside as “kid’s stuff.”

But while evildoers may not appear in the real world painted up as sadistic clowns or riding on the Goblin Glider, the world has never ceased its need for heroic men who are willing to come to the aid of those in danger and stand up for what is right.

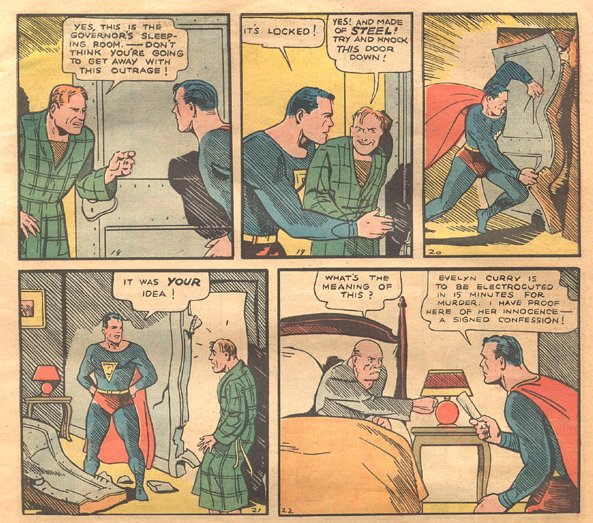

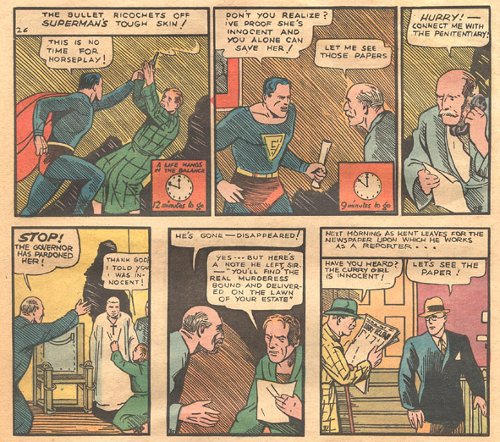

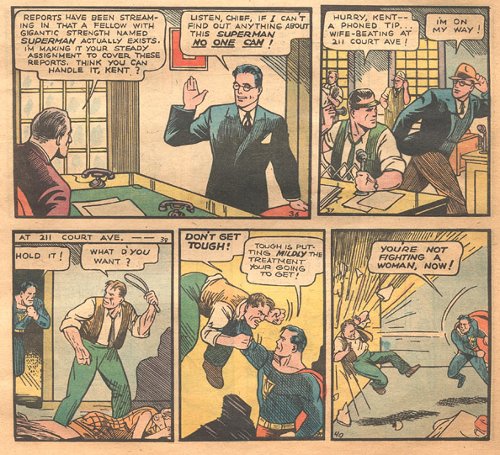

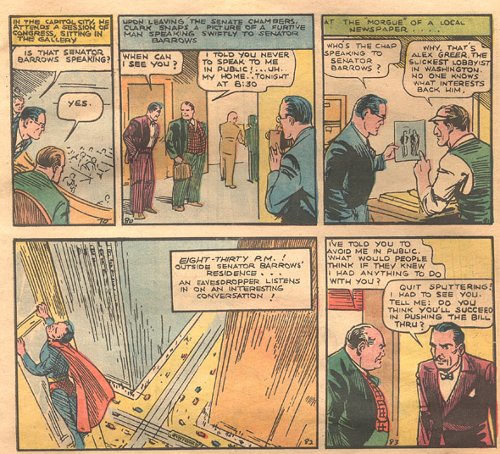

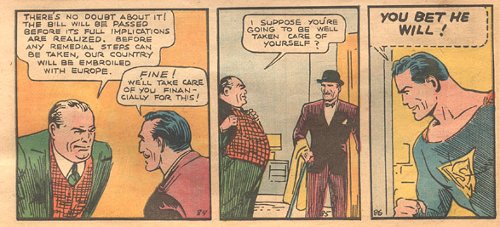

While we now think of the Man of Steel battling super villains like Lex Luthor and Bizarro, when Superman was introduced in 1938, he was a champion of the little guy, fighting for social justice and morality and against corruption. As you can see in Superman’s debut in Action Comics #1, the “Champion of the oppressed. The physical marvel who had sworn to devote his existence to helping those in need” was concerned with the execution of innocent people, corrupt legislation, and even wife-beating.

To a people demoralized by the Great Depression, this was truly a hero for the time. And amidst our current recession of both finances and morale, it’s the kind of hero we need today. Most encouragingly, while we probably shouldn’t go about fighting injustice by busting into the governor’s mansion, it’s the kind of heroism that is within the reach of every man.

But for many of us, engaging in even this kind of heroism seems as difficult as running faster than a speeding train.

What Makes a Man a Hero?

Why do some men stand by and watch an injustice or an emergency take place without doing anything, while other men spring to action and save the day?

Two researchers, Zeno Franco and Phillip Zimbardo, have taken up these very questions. Many of you might be familiar with Dr. Zimbardo’s famous 1971 Stanford Prison Experiment that showed good people turning into sadistic tyrants when placed in a position of authority over other human beings. However, one of the interesting observations of the experiment was that “good guards” did exist in the make-believe prison. These guards didn’t abuse or insult the student-prisoners, like the “evil guards” did, but they never tried to stop the abuse, either. Thus, the good guards actually ended up facilitating abuse by not taking action.

All that is necessary for evil to triumph is for good men to do nothing. ~ Edmund Burke

The Stanford Prison Experiment demonstrated that given certain circumstances and social pressures, normal, decent people can end up doing unspeakable things.

But it also showed that these same circumstances and social pressures can cause men to commit a different but equal wrong: not taking action when action is required.

We see this wrong all the time. I’m sure we can all remember a time when we saw another human needing assistance, but we simply stood by and did nothing. I’ll admit it. I’ve seen car accidents and just drove by. I’ve also seen people treated unfairly but didn’t say anything because I feared I would suffer social ostracization.

Forty years after his infamous Stanford Prison Experiment, Zimbardo has taken up the task of finding out what causes individuals to move from cowardly inaction, to heroic action. After analyzing the deeds of heroes both big and small, Zimbardo along with his research partner, Dr. Franco, argue that heroic individuals have a robust heroic imagination.

How to Develop Your Heroic Imagination

According to Zimbardo and Franco, the heroic imagination is “the capacity to imagine facing physically or socially risky situations, to struggle with the hypothetical problems these situations generate, and to consider one’s actions and the consequences.” It’s the ability to see oneself as a hero and capable of heroic action before the need for heroic action arises.

Okay, great. Heroic people can imagine themselves doing heroic things. But are some people born with more or less heroic imagination? If I was born with a weak heroic imagination, am I doomed to a lifetime of wienerdom?

Zimbardo argues that while some individuals may have a natural tendency for heroic behavior, all of us have the capacity to nurture and grow our inner hero. It’s a not a static characteristic. In his article “The Banality of Heroism,” Zimbardo lays out five concrete steps we can all take to develop our heroic imagination and thus be ready to take action when action is required.

Below are the five traits that will strengthen your heroic imagination and propel you into heroic action.

1. Maintain constant vigilance for situations that require heroic action. Every day we have opportunities to take a stand and be heroes. Sure, we probably won’t have to land a plane or fight off a ruffian, but we can be heroes by sticking up for a student being bullied by one’s peers, blowing the whistle on a supervisor who is engaging in shady and unethical business practices, or stopping to help a stranded driver. The more you develop your ability to spot situations to be heroic, the more chances you’ll get to take heroic action.

2. Learn not to fear conflict because you took a stand. When you see a situation that requires action, don’t wussy out because you’re afraid of what other people will say or do. A real man doesn’t give a damn if some people get upset or uncomfortable with doing the right thing. Don’t be afraid to stand by your principles and live with integrity.

3. Imagine alternative future scenarios beyond the present moment. We often fail to act because we’re too short-sighted. We think about the immediate consequences rather than the long-term ones. Sure, you might lose your job because you blew the whistle on unethical practices by your company. But think about the the long-term consequences if you don’t act. How many more people will be hurt if you don’t out your employer? Will you be able to look yourself in the mirror 20 years down the road knowing you didn’t do the right thing because it would have caused a couple of months of financial hardship?

Zimbardo also suggests we not only look to the future, but that we should “keep part of our minds on the past” as well. Study the lives of great men who performed heroic deeds. Studying their noble deeds will instill in us the virtues and values required for a heroic imagination and inspire us to take heroic action when needed.

4. Resist the urge to rationalize and justify inaction. Inaction is easy because it’s so easy to rationalize. The “bystander effect” is a perfect example of this. The bystander effect occurs when an emergency situation occurs in a large group of people and no one takes action to remedy the situation because they rationalize that someone else will take care of it.

Don’t be that person.

Instead of looking for ways to rationalize inaction, train yourself to rationalize action. Instead of thinking, “I won’t do anything because someone else will take care of it,” start thinking “I must take action because no one else will.”

5. Trust that people will appreciate heroic (and frequently unpopular) actions. In point number two, we’re told not to fear the conflict that might arise from doing the right thing. Conversely, we should also develop a confidence that people appreciate and honor heroic action. While your action may be unpopular at first, people eventually come around and appreciate and recognize true heroes.