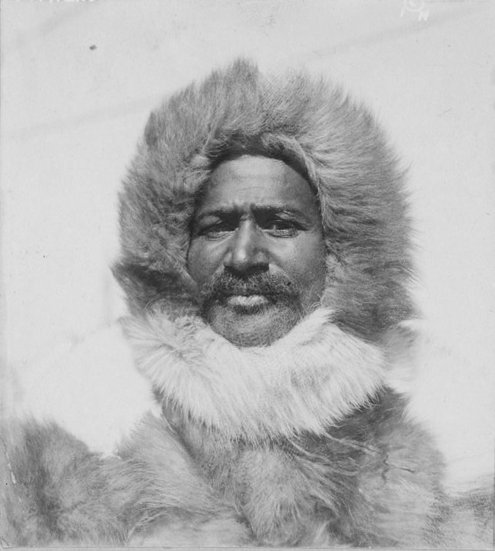

“The Captain had gone, Commander Peary and I were alone (save for the four Esquimos), the same as we had been so often in the past years, and as we looked at each other we realized our position and we knew without speaking that the time had come for us to demonstrate that were the men who, it has been ordained, should unlock the door which held the mystery of the Arctic.” -Matthew Henson

When you think of history’s great Arctic explorers, what names spring to mind? Ernest Shackleton? Robert Peary? How about Matthew Henson?

Matthew who?

While Robert Edwin Peary’s name has come down to us as the first to set foot on the northernmost part of the world (although not without controversy), the story of the man who truly made that expedition possible has often been overlooked.

For a long time, what lay at the very top of the world was a complete mystery. Was there land there? Just ocean? Was it a place inhabited by mystical monsters and sea creatures? Even as an accurate picture of the North Pole began to emerge-that it was essentially composed of floating ice-the race to claim this piece of unexplored frontier remained fiercely competitive.

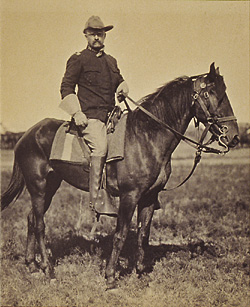

Robert Peary’s hunger for the Pole, and for fame, was insatiable. He made 7 grueling Arctic expeditions between 1886 and 1909. The only man who accompanied him on each of those expeditions was Matthew Henson. Together they faced the harshest of Arctic challenges and together they planted the American flag at the Pole.

But Peary, who author Fergus Fleming called “the most unpleasant man in the annals of polar exploration,” had no interest in sharing the glory of the accomplishment with any other man, especially a black man. Years before his quest for the Pole commenced, Peary had written to his mother, “I must be the peer or superior of those about me to be comfortable.”

And Henson made Peary very uncomfortable indeed. While Peary viewed him as an inferior, it was Henson who was essentially the de facto leader of the Polar expeditions-Henson who took care of the other men, dogs, and supplies; Henson who spoke the Eskimo language; Henson who fixed the sledges (tough sleds) and used those sledges to pull Peary, who’s walking ability was hampered by the loss of 8 of his toes to frostbite on a previous expedition, to and from the Pole. Without the skills of Matthew Henson, the American flag would not likely have been the first atop the world.

Yet during the 1909 expedition, Peary had secretly planned to leave Henson behind once they got close to the Pole, so that he could claim farthest north all for himself. But the expedition made better time than he realized (it’s hard to keep track when you’re laying in a sled), and the team landed at the Pole before he had a chance to ditch the others.

Crestfallen that he had to share the glory of the moment with 4 Eskimos and a black man, Peary immediately ceased to speak to Henson, the man who had saved his life on a previous expedition and had remained absolutely loyal to him for 22 years when every other member of the expeditions had left because of Peary’s insufferable personality and demands. Unwilling to share the resulting fame, Peary forbade Henson to write, lecture, or grant interviews about the expedition. Henson had used his own camera to take 100 pictures on the trip and used his own money to develop them. Peary asked to borrow these pictures and then never gave them back.

Of course, this left Peary free to lecture and write in abundance, and paint himself at the sole hero of the expedition, effectively eclipsing Henson’s role. But Henson deserves a place in the pantheon of the world’s greatest explorers and from his life we can glean several important lessons in manliness.

Don’t settle for your lot in life. Matthew Henson was born in 1866 in Maryland. Before he would turn 7, both of his parents passed away, and he was sent to live with an uncle. Even at the tender age of 12, Henson knew he wanted more from life then the largely menial jobs available to African-Americans of the time. The young lad struck out for Baltimore and headed for the docks. He got hired on a ship as a cabin boy and sailed for China. Life on the ocean suited him well, and he spent the next several years of his life sailing all around the world, learning manly skills and the virtue of hardihood.

When Peary met Henson in 1888, he was duly impressed with this experienced seaman and his “greater than average intelligence and pluck.” After the two spent some time exploring South America, Peary asked Henson to accompany him on their first Arctic expedition in 1891; Henson accepted.

By constantly broadening his horizons, Henson made a habit of defying expectations. Slavery had been abolished less than 30 years before, and not only did racism keep African-Americans from most pursuits, it was widely believed that blacks could not survive in the harsh cold of the Arctic climate. Henson would boldly prove otherwise.

Immerse yourself in the culture. While Peary was one of the first explorers to incorporate many of the Eskimo ways of traveling and dressing, and while he fathered a child with an Eskimo woman (as did Henson), he saw that people as a race of inferior children. He never bothered to learn their language. Henson, on the other hand, spent much of his time getting to know the Eskimos and enjoying their culture. He became fluent in Inuit, likely making him the only American at the time to know that language. He respected them and they respected him:

“Many and many a time, for periods covering more than twelve months, I have been to all intents an Esquimo, with Esquimos for companions, speaking their language, dressing in their clothing, living in the same kind of dens, eating the same food, enjoying their pleasures, and frequently sharing their griefs. I have come to love these people. I know every man, woman, and child in their tribe. They are my friends and they regard me as theirs.”

Understanding the Eskimo culture allowed Henson to communicate with the Eskimos who accompanied them on the expeditions and pick up valuable survival tips that helped make the expedition a success. To this very day, the Inuit of Greenland still tell stories and sing of Mahripaluq (“Matt, the kind one”).

Cultivate true grit. While we often romanticize the lives of great explorers, the reality of day to day life on an expedition was bleak and grueling. At the northern most part of the world, temperatures would drop to 60 degrees below zero, with winds capable of making it feel like 125 below. These same winds would pick up 100 pound rocks and hurl them through the air, smashing and killing men in the blink of any eye.

And while you might imagine the Pole as a sheet of flat ice, it’s actually studded with 60-100 foot high ridges and dotted with sections of “rubble-ice” which had to be cleared away with pickaxes and was capable of splitting the sledges into several pieces. The men traveled for 13 hours at a time, with the ice stretching as far as the eye could see. While the march itself was physically draining, the men actually preferred moving over sleeping. Sleeping in igloos on blankets right on top of the snow, the men would wake up every hour and have to beat their extremities to keep the circulation going. And the noise of howling wind and cracking ice was positively deafening.

When they would come to a lead (an open channel of water between the ice), they would be forced to wait for the temperature to drop and a thin layer of ice to form. Then they would carefully cross with their dogs and sledges, watching little cracks appear, barely able to breathe knowing the next step could plunge them through the ice and to a freezing death in the water. Henson did take a dip once but was luckily pulled immediately out of the water. As soon as he changed clothes, he was off on the march once more.

It takes a man of grit to face down these obstacles, but Henson had the right stuff.

Cultivate your drive. Clearly, Arctic exploration was no picnic. Just one of these grueling expeditions would sap most men’s motivation to ever leave home again; that Henson was able to overcome the pull of home and hearth not once but 7 separate times is a testament to his drive and resolve. That resolve would be sorely tested time and time again, but probably no more so than on an expedition to reach the northeastern border of Greenland in 1895. When the team departed Anniversary Lodge, they had 3 sledges and thirty-seven dogs. When they returned 3 months later, they had 1 sledge and 1 dog left. Ragged, hungry, frozen, and exhausted, Henson described the harrowing experience as a “long race with death.” It took him months to regain his health afterward. When he left in a ship back to the States he resolutely vowed to never, ever again leave his “happy home in warmer lands.” But when summer came around several months later, he was once more northward bound with Peary.

Of the many bright-eyed men who joined the expeditions with gusto only to quit halfway through, he said,“I have seen too many enthusiastic starters, and I am sorry to say some of them did not finish well.” Not Henson. He saw the quest through to the end and would not be deterred until the goal was attained.

Feed your body and your mind. Henson understood that mental strength was just as important as physical strength when facing life’s challenges. Man cannot live on pemmican alone. When he wasn’t working, he spent the long dark nights of the Arctic winter with his books. On the voyage to Greenland and the initial stages of the expedition, he brought along books by Peary himself, Dicken’s Bleak House, Kipling’s Barrack Room Ballads, and the poems of Thomas Hood. When supplies had to be reduced for the final push, he packed just the Bible in his sledge. During the journey, Henson traded books with the other men and engaged in lively literary debates around the campfire. Henson was also a religious journal keeper, making entries whenever time and conditions allowed.

Make yourself indispensable. To the naysayers who criticized the inclusion of a black man on a Arctic expedition, Henson didn’t have to say a word; he simply went to work. Henson was an Arctic Renaissance man. Booker T. Washington, a Henson admirer, summed it up well:

“During the twenty-three years in which he was the companion of the explorer he not only had time and opportunity to perfect himself in his knowledge of the books, but he acquired a good practical knowledge of everything that was a necessary part of the daily life in the ice-bound wilderness of polar exploration. He was at times a blacksmith, a carpenter, and a cook. He was thoroughly acquainted with the life, customs, and the language of the Esquimos. He himself built the sledges with which the journey to the Pole was successfully completed. He could not merely drive a dog-team or skin a musk-ox with the skill of a native, but he was something of a navigator as well. In this way Mr. Henson made himself not only the most trusted but the most useful member of the expedition.”

In addition to the skills BTW mentions, can also be added Henson’s talents in trading, hunting, dog-training, barbering, tailoring, and soldering. He made repairs to the sledges every day, and when the ice shattered them into pieces, he could create a new working sledge from the remnants. And he did it all while Arctic storms raged around him. He taught himself these skills by carefully observing others and trying it out until he had it mastered.

In the 1920 issue of National Geographic, Admiral Donald B. MacMillan said, “He was indispensable to Peary and of more real value than the combined services of all four White men.” This indispensability, coupled with manly grit and determination, guaranteed him a place on the expedition and in the history books.

Sources:

A Negro Explorer at the North Pole, the autobiography of Matthew Henson

Ninety Degrees North by Fergus Flemin