“Only those are fit to live who do not fear to die.”

-Theodore Roosevelt

Sailing out of the New York harbor, Theodore Roosevelt had little indication that the journey he was embarking on, which he had referred to as “a delightful holiday” with “just the right amount of adventure,” would be the hardest test of his notoriously strenuous life. Reeling from his recent defeat as the Progressive Party’s nominee in the 1912 presidential elections, Roosevelt needed to get away. Near the end of his last term as President, Roosevelt had been constantly petitioned by old friend and aspiring explorer Father John Zahm to join him on a South American river adventure. At the time, Roosevelt had passed on the offer, noting that he was more interested in setting out on safari in Africa, which he immediately did when he left office. Now, ready to temporarily leave politics behind and start off on another adventure, he let Father Zahm know that the South America trip was on and to begin preparations.

Originally, Father Zahm had planned a trip down a well explored river in the Amazon. While such a trip still had inherent danger, there were no major risks involved, and a leisurely pleasure cruise just is not what the old Bull Moose had in mind. When a government official casually suggested that he instead seek out the unexplored Rio da Dúvida (River of Doubt), T.R. jumped at the opportunity. The change in plans came as a shock both to Brazilian officials as well as the American Museum of Natural History, which was sponsoring the expedition. After all, having a former head of state die on your watch is usually considered to be rather bad press. With the uncertainty of what dangers the expedition would hold, it was immediately clear to the men that death was a very real possibility.

“It may be said with confidence…that in all South America there is not a more difficult or dangerous journey than down the [River of Doubt].”

-Frank Chapman, Curator for American Museum of Natural History at the time.

True to its name, the River of Doubt was a complete mystery, its length and course not listed on any map. It was likely to hold not just the usual Amazonian combination of dangers and disease, but most certainly potentially hostile Indian tribes as well. It was certainly not the way most former Presidents would choose to spend their retirement, but then again, T.R. wasn’t much like most former presidents. Prior to the expedition’s commencement, the head of the American Museum of Natural History, Henry Osborn, wrote Roosevelt several times pleading with him to abandon his perilous new plans and return to the old itinerary. Roosevelt, in a letter to Frank Chapman, responded to Osborn’s request:

“Tell Osborn I have already lived and enjoyed as much of life as any nine other men I know; I have had my full share, and if it necessary for me to leave my bones in South America, I am quite prepared to do so.”

Into the Unknown

It quickly became clear that the inexperienced Father Zahm was not capable of organizing this new expedition, and a new guide was sought out. The Brazilian government provided Roosevelt with perhaps the most capable guide in all of South America, Colonel Cândido Rondon. Rondon was a well known and highly respected military officer known who had for years been leading an effort to install telegraph wires across the Amazon. It was widely accepted that no man was more familiar with the Amazon and her dangers, including those presented by indigenous tribes, than Cândido Rondon.

With all the final preparations made, the expedition set out into the wilds of the Amazon. It would take them at least two months just to reach the headwaters of the river, traveling first by steamboat on the Paraguay River into the Brazilian Highlands to a small frontier town, at which point they would switch from steamboat to mules. From this point forward, every step they took widened the gap between the explorers and the civilization they were leaving behind. Setting off on mule back, the team would have to traverse over 400 miles of wilderness before they reached the Rio da Dúvida, and only then would the expedition truly commence.

By the time the men reached the River of Doubt, it was clear to Roosevelt and Rondon that several of the men were ill prepared for the excursion. Even worse, it was increasingly evident that they were ill supplied for the journey they were about to embark on. The leaders made the decision to split the team. Several members of the team, instead of descending the unknown River of Doubt, would instead set out for the Rio Aripuanã, which Colonel Rondon believed joined the River of Doubt near its end. While this separation meant dividing the supplies, it also guaranteed the main team greater speed as they descended the unknown river. The final members that were to make up the Roosevelt-Rondon River of Doubt expedition included Roosevelt, his son Kermit, Rondon, his assistant Lyra, the team physician Dr. Cajazeira, and naturalist George Cherrie. The team was supplemented by the addition of 16 camaradas, local Brazilians hired by Rondon to work as paddlers and trailblazers.

Taking stock of their provisions, the men realized that the supplies intended for the original itinerary were shockingly inadequate for the new journey. Father Zahm had gone to great lengths to stock the original expedition with as many creature comforts as possible, seeking the approval of the former President. Now, embarking on a journey into the unknown, Roosevelt was anything but impressed by the rations. Where he had hoped to find various dried foodstuffs and salted meats, he instead found varieties of tea, sweets, and food that would likely spoil on this new, longer journey. Organizing what was useful and discarding the rest, Roosevelt and Rondon realized that the expedition was no longer just a journey into the unknown, it had now become a race against time. To further complicate matters, the expedition had been forced to abandon the lightweight canoes they had intended to use, and now only had primitive dugout canoes, which they knew were not only inadequate, but would likely not survive the rapids they would inevitably face. Nonetheless, the expedition began its descent of the River of Doubt on February 27, 1914. Before the end, they would face every imaginable peril, and the Bull Moose himself, who had defied death on so many occasions, would come face to face with his mortality.

The Journey Begins

In every dark corner of the Amazon lies a hidden peril. The dugout canoes the expedition used floated only a few inches above the surface, leaving the men acutely aware of their proximity to the fifteen foot caimans, school bus length anacondas, and razor toothed piranhas (which T.R. called “ferocious little monsters”) lurking just beneath the surface of the water. The river frequently rose and fell, was studded with perilous rapids, and sometimes narrowed to a mere 2 yard pass between sheer stone walls on either side. No one on the expedition had any idea of what danger lay ahead, waiting around every curve. Dry land proved to be equally threatening, hosting swarms of disease carrying insects, venomous snakes, poison arrow frogs, and the elusive jaguar. Of all the dangers anticipated by the men, however, none weighed more heavily on their minds than the likelihood of stumbling upon a village of potentially hostile natives who had never before laid eyes upon outsiders. The region they were traveling through harbored several known cannibalistic tribes, as well as numerous and yet unknown populations of natives.

“Within such an intricate world of resourcefulness, skill, and ruthless self-interest, refined over hundreds of millions of years, Roosevelt and his men were, for all their own experience and knowledge, vulnerable outsiders. Most of the men were veteran outdoorsmen, and many of them considered themselves masters of nature. They were stealthy hunters, crack shots, and experienced survivalists, and given the right tools, they believed that they would never find themselves in a situation in the wild that they could not control. But as they struggled to make their way along the shores of the River of Doubt, any basis for such confidence was quickly slipping away. Compared with the creatures of the Amazon, including the Indians whose territory they were invading, they were all – from the lowliest camarada to the former president of the United States – clumsy, conspicuous prey.”

–The River of Doubt by Candice Millard

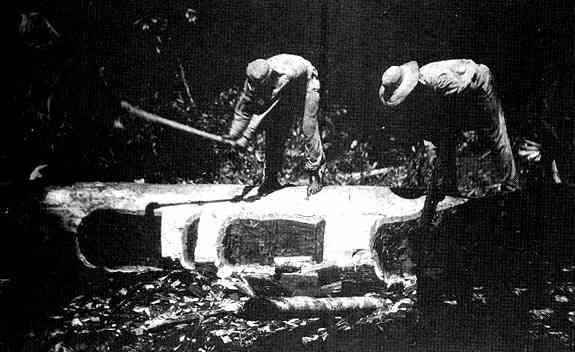

The expedition’s progress was initially quite slow. On the first day they managed to cover only six miles, considerably less than they were hoping for. In the following days they were unable to quicken their pace, and by the second week they were acutely aware of the fact that they would run out of food well before they ran out of river. Until this point they had avoided the rapids themselves by walking along the banks and guiding the heavy canoes laden with supplies through the whitewater with ropes. While they had some success with this system, disaster eventually struck when two canoes broke loose, leaving the men to helplessly watch as their canoes and supplies were smashed on the rocks of the river and washed downstream. With the loss of the canoes, the men could no longer move forward, and turning back was now an impossibility as well. They were forced to stop for several days and build a new, larger canoe to replace the two that were lost. Having completed this, the men then resorted to running the rapids they encountered in their canoes in an effort to make up lost time.

Death on the River

Eventually they came upon a series of rapids which led to the edge of a 30 foot waterfall. Rondon wisely deemed the rapids impassable and began to prepare for the portage around. Kermit Roosevelt, however, made the brash decision to attempt to seek out a route around the rapids. With two camaradas in his canoe, he set out for a small island in the middle of the rapids. Quickly realizing that Rondon was right and the rapids were indeed impassable, he told the paddlers to return to the shore. On attempting to navigate the rapids for a second time, however, the men lost control of the canoe and were drawn into the heavy whitewater. Theodore Roosevelt could only watch in horror as his son and the men were pushed downstream and over the edge of the falls. Rushing down to the base of the falls, the men of the expedition were relieved to find Kermit and one of the camaradas alive, but any feelings of relief were soon dashed. One of the camaradas had been sucked downstream and was never seen again.

The Locals Make Themselves Known

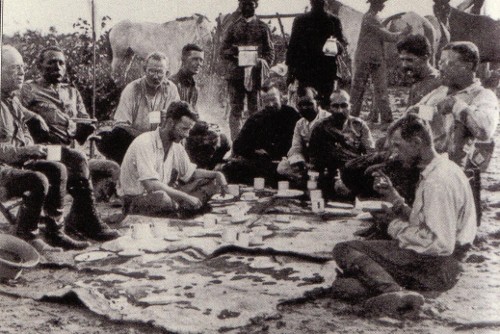

Roosevelt on the left with a deer he had shot. Col. Candido Rondon is on the right.

Several days later, while the men set up their evening camp, Rondon set out with his dog and rifle in search of game to supplement their meager rations. A monkey call ahead in the darkness of the forest canopy put him on alert, and his dog quickly ran towards the call. Not a moment later Rondon heard the dog cry out and realized he had been drawn in by Indians mimicking monkey calls in an attempt to lure him. The sight of his dog appearing from the jungle ahead of him with two large arrows in his side confirmed his suspicions, and he quickly retreated to camp and put the men on their guard. They had suspected they were in the lands of an unknown and likely hostile tribe, and now they were sure of it. Later expeditions would confirm that the tribe living along the river was both violent towards outsiders and cannibalistic.

A Race Against Time

The expedition continued to be plagued by misfortune. The loss of two more canoes in the rapids and the lack of suitable trees for making new dugouts forced them to split up. Several members would have to hack their way by machete along the overgrown riverbank while the rest floated on the river alongside, which only slowed progress even more. By the 90 mile mark, they had consumed over a third of their provisions, and Rondon believed that they would need to travel at least five times that distance before they would reenter charted lands and civilization. Their supplies and remaining canoes were now, more than ever, in need of protection. When two of the canoes became jammed between rocks in a section of whitewater, Roosevelt quickly jumped into the water to free them before they were lost. While attempting to cross the rapids he slipped, opening a large gash on his thigh. Back in the White House, such a wound would have been quickly stitched up, and he would have been able to return to his business. In the Amazon, however, the wound was potentially a death sentence.

The expedition doctor treated the wound immediately, but the men feared the worst. A serious infection set in overnight, accompanied by an outbreak in malarial fever, leaving Roosevelt with a high fever and unable to walk. For the next several days Roosevelt’s condition continued to worsen, his fever skyrocketing to 105 degrees as he drifted in and out of consciousness. Eventually he began to move in and out of a trancelike state, eerily repeating over and over again the opening lines of Coleridge’s Kubla Khan, “In Xanadu did Kubla Khan, A stately pleasure-dome decree.” At his side was always either the doctor or his son Kermit, who was adamant that his father would walk out of the jungle alive and well. In one of his lucid moments Roosevelt took stock of the situation and realized he did not stand a chance and had now become a hindrance to the expedition, thus risking the other men’s lives. Drawing his son and Cherrie to his side, he argued his case:

“Boys, I realize some of us are not going to finish this journey. Cherrie, I want you and Kermit to go on. You can get out. I will stop here.”

Roosevelt’s admission of defeat did not come as a surprise to the men, who were well acquainted with the character of the man. This was not a decision born out of cowardice or lack of fortuity. This was the ultimate sacrifice. Roosevelt knew that his life was not worth more than those of the rest of the expedition and was simply taking himself out of the equation to prevent further tragedy. Kermit and the men refused to comply with his wishes, however, and Roosevelt quickly realized that even if he were to die, Kermit would never leave his body in the Amazon. Any delay caused by his illness was clearly preferable to the option of dragging a body out of the wilderness. Thus, Roosevelt pushed on.

Blood in the Water

Roosevelt’s condition continued to worsen for several days, yet the men had to keep moving. Eventually he was forced to lie prone in one of the dugouts, unable to contribute to the expedition in any way. For Roosevelt, who had championed hard work and the strenuous life since childhood, the loss of his vigor and ability to aid the men around him was very nearly a fate worse than death. Even when driven to the edge of his mortality, however, Roosevelt was able to spring to action if the situation required it.

While most of the camaradas had proven themselves to be extremely reliable workers and good companions, the leaders of the expedition had quickly realized that one of the men was a dangerous character. On expeditions, few crimes carried heavier consequences than the stealing of rations, as one of the men had secretly been doing for weeks. When confronted by another camarada, the man quietly returned to camp, grabbed a rifle, walked back to his accuser and shot him through the heart. The men in camp heard the shot, but just assumed it was one of the team members hunting and began to set their hopes on meat for dinner. When several camaradas ran into camp crying murder, however, the mood quickly changed. Even in his terrible condition, Roosevelt could not tolerate such injustice. To the amazement of the men around him, he exploded out of bed, grabbing his rifle and setting out for the scene of the crime. Upon arrival they found the body of the unfortunate camarada and the gun used to kill him, but the murderer was nowhere to be found. Realizing that no punishment was greater than being alone and unarmed in the wilds of the Amazon, they simply left him to his fate.

An Act of Desperation

It was becoming clear that Roosevelt would not survive another day without allowing the doctor to attempt surgery on his leg. Up until this point, Roosevelt had refused an operation, but now it had become inevitable. Lying Roosevelt down in the mud on the bank of the river surrounded by swarms of insects attracted to the gaping wound, the doctor prepared to remove the dead flesh and clean the wound. Lacking even the most rudimentary medical equipment, the doctor could not provide Roosevelt with even a small dose of painkillers, leaving the former President fully conscious and acutely aware of every cut of the knife. True to form, Roosevelt did not even wince as the doctor carried out the surgery, much to the disbelief of the men surrounding him. Even with his body battered and broken, Roosevelt’s will was as strong as ever.

Civilization

It was not long after that the men began to see signs of civilization. Rubber tappers had been moving deeper and deeper into the jungle with every passing year in an effort to strike it rich in the Amazon’s equivalent of a gold rush. The men of the expedition began seeing signs of these rubber men and finally came upon several small huts which housed rubber men and their families. At first, the rubber tappers and their families reacted with fear at the sight of the strange looking men coming from upriver and assumed the worst, Indians. Fortunately, the men of the expedition were able to identify themselves before the rubber men opened fire on them, and they were then welcomed into their homes.

The most difficult leg of the journey was over, but they still had a considerable distance to travel. Fortunately for the men, the rubber tappers were very generous, providing them with food and supplies and even trading lightweight canoes for their dugouts to aid their journey. Several days later, the men saw in the distance what must have been the sweetest sight of their entire lives. Flapping in the breeze side by side were the Brazilian and American flags, a telltale sign that they had reached the meeting point of the River of Doubt and the Rio Aripuanã, where the other team they had left months earlier were waiting to greet them. They had journeyed on the Rio da Dúvida for a staggering 950 miles.

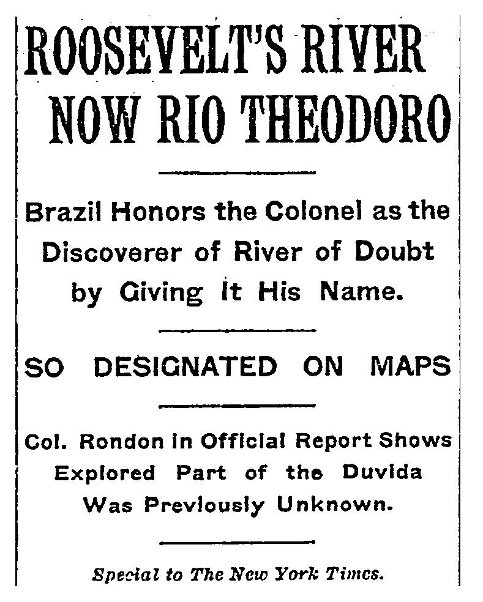

As the Brazilian leader of the expedition, Cândido Rondon was responsible for naming the newly explored river, which he christened the Roosevelt River, now known locally as the Rio Theodoro.

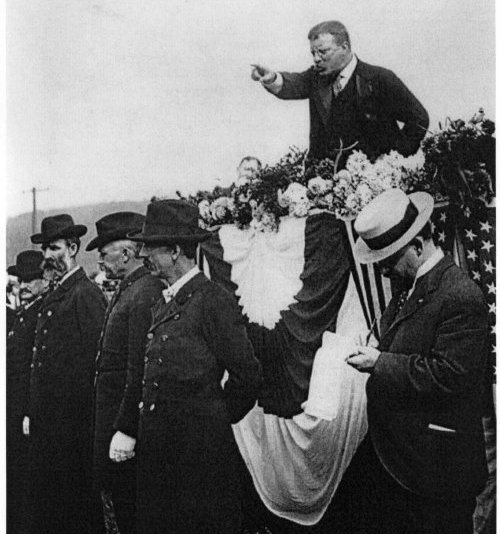

T.R. remained gravely ill for weeks following the end of the expedition and never fully recovered. The effects of a starvation diet and the fever that plagued him on the journey were evident; Roosevelt had lost nearly sixty pounds and had aged considerably. His physical vigor and endurance were all but gone, and he was now forced to at least temporarily support himself with a cane. Not one to be kept down, however, Roosevelt continued to push his limits. When he had recuperated enough to complete the voyage home, he was greeted from the deck of the ship by cheering crowds in New York harbor. A daring few criticized the efforts of the expedition, some even labeling its achievements a lie. Roosevelt, astounded at these outrageous accusations, set out on a speaking tour in America and Europe to support his claims. As you would expect, every critic was silenced. No one messes with a Bull Moose and gets away with it.

T.R. remained gravely ill for weeks following the end of the expedition and never fully recovered. The effects of a starvation diet and the fever that plagued him on the journey were evident; Roosevelt had lost nearly sixty pounds and had aged considerably. His physical vigor and endurance were all but gone, and he was now forced to at least temporarily support himself with a cane. Not one to be kept down, however, Roosevelt continued to push his limits. When he had recuperated enough to complete the voyage home, he was greeted from the deck of the ship by cheering crowds in New York harbor. A daring few criticized the efforts of the expedition, some even labeling its achievements a lie. Roosevelt, astounded at these outrageous accusations, set out on a speaking tour in America and Europe to support his claims. As you would expect, every critic was silenced. No one messes with a Bull Moose and gets away with it.

“Far better it is to dare mighty things, to win glorious triumphs, even though checkered by failure, than to rank with those poor spirits who neither enjoy much nor suffer much, because they live in that grey twilight that knows neither victory nor defeat.”

-Theodore Roosevelt

Listen to our podcast with River of Doubt author Candace Millard: